For the previous entry in this series, click here.

The first Native Americans to visit England were brought over by English mariners for display as curiosities. There was no shortage of Englishmen interested in viewing see Brazilian "princes" or Inuit hunters, even if it meant paying for the privilege. Shakespeare observed that men who "will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar...will lay out ten to see a dead Indian" (The Tempest, Act II, Scene ii.)

A change occurred in the 1580s, after Queen Elizabeth I chartered the first English colonial venture to North America, the Virginia Company. In 1584 the company's chief proprietor, Sir Walter Raleigh, dispatched a vessel to survey the North American coast, look for settlement sites, and procure local Indians who could be trained as interpreters. The ship returned later that year with two Algonquian werowances (or petty chiefs), Manteo and Wanchese, from Croatan and Roanoke Islands off the coast of present-day North Carolina. The chiefs had come voluntarily, probably because they and their kinsmen had heard of other European incursions in the area (like the Spanish Jesuit mission in present-day Virginia) and wanted to gather intelligence on these new intruders.

The two chiefs resided for several months in London, more specifically at Durham House, the royal mansion that Elizabeth I had loaned to Walter Raleigh. There Raleigh's friend Thomas Hariot learned some of the visitors' language and prepared a rudimentary Algonquian syllabary for future colonists, along with a 36-letter alphabet for spelling Algonquian words. Hariot also taught the Indians a fair amount of English.

In the spring of 1585 Manteo and Wanchese returned home on one of the ships that the Virginia Company sent to Roanoke to establish its first settlement. Manteo subsequently became a close ally of the Roanoke colonists, probably because he regarded them as useful trading partners - and because his continued relationship with the English strangers provided him with political prestige. Wanchese, by contrast, turned his back on the English, probably because his people had to leave Roanoke Island after the colonists proved quarrelsome and warlike.

In 1586 Manteo returned to England with a Croatan companion, Towaye. The two men lived in London for nearly a year, and returned to Roanoke in 1587 with the second major party of Virginia Company colonists. Meanwhile, another Algonquian captured by Virginia Company officer Richard Grenville arrived in England in the fall of 1586. Grenville brought the captive to Devonshire, where he was baptized (March 1588) as "Rawly, a Wynganditoan." Perhaps Grenville intended to train Rawly as a translator, but he soon died and was buried in Bideford Parish, Devonshire, in April 1589.

Back in the Roanoke colony, Manteo remained a strong English ally and was baptized by colonial officials in August 1587. His subsequent fate is unknown, but Alden Vaughan speculates that his kinsmen, or other coastal Algonquians, may have killed him after one of many skirmishes between the trigger-happy English settlers and their Indian neighbors. As for the Roanoke colonists, it seems likely that they left their island early in 1588 and (as they had been planning to do) relocated to the shores of Chesapeake Bay. The Virginia Company lost contact with the colony during the Armada crisis of 1588 and the long Anglo-Spanish war that followed; relief expeditions in 1590 and 1603 found no trace of the colonists but were probably looking in the wrong place. There is documentary evidence that the relocated colonists were killed or captured by warriors of the Powhatan confederacy in 1607, just as another English expedition arrived in the Chesapeake to establish the colony of Jamestown. (Alden Vaughan, "Sir Walter Ralegh and His Indian Interpreters," William and Mary Quarterly 59 [April 2002]), 346-357.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Friday, December 08, 2006

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Pine Trees and Penobscots

In my post of June 9th, I discussed Mark Peterson's article on the Pine Tree shilling, the first coin minted by an American colonial government, and its significance as a symbol of Massachusetts's imperial ambitions. A couple of weeks ago I discovered another historical use of the Pine Tree shilling: as an ad hoc medal given to Indians to display (and to secure) their friendship to the colony.

In January 1714 General Francis Nicholson held a peace conference (most likely in Nova Scotia, of which he was the governor) with 5 sachems of the Penobscot, Norridgewock, and Kennetuck divisions of Abenakis. The general presented each man with two Pine Tree shillings, placing one in the recipient's hand and the other in his mouth, that he might never act or speak against the English Crown or its subjects. He declared that the pine tree on the coins symbolized the unity of the English and Abenakis - "they and the English should be like that tree - but one root tho' several branches" - and noted that it was always green, symbolizing truth. (James Baxter, ed., Documentary History of the State of Maine [23 volumes; Portland, ME, 1869-1916], Vol. 23, pp. 53-54.)

Nicholson did not record the Abenakis' reaction, but it's likely that they understood what they were receiving - the Woodland Indians were sufficiently familiar with coins by the early 18th century that some were learning how to counterfeit them. (Colin Calloway, New Worlds for All [Baltimore, 1997], pp. 47-48.) It also seems likely that the sachems were unimpressed with the display: shillings were not valuable coins and Nicholson's metaphors were ersatz.

In January 1714 General Francis Nicholson held a peace conference (most likely in Nova Scotia, of which he was the governor) with 5 sachems of the Penobscot, Norridgewock, and Kennetuck divisions of Abenakis. The general presented each man with two Pine Tree shillings, placing one in the recipient's hand and the other in his mouth, that he might never act or speak against the English Crown or its subjects. He declared that the pine tree on the coins symbolized the unity of the English and Abenakis - "they and the English should be like that tree - but one root tho' several branches" - and noted that it was always green, symbolizing truth. (James Baxter, ed., Documentary History of the State of Maine [23 volumes; Portland, ME, 1869-1916], Vol. 23, pp. 53-54.)

Nicholson did not record the Abenakis' reaction, but it's likely that they understood what they were receiving - the Woodland Indians were sufficiently familiar with coins by the early 18th century that some were learning how to counterfeit them. (Colin Calloway, New Worlds for All [Baltimore, 1997], pp. 47-48.) It also seems likely that the sachems were unimpressed with the display: shillings were not valuable coins and Nicholson's metaphors were ersatz.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Voyagers to the East, Part X

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

From the sixteenth-century Spanish viewpoint, North America was a backwater. Explorers like De Soto and Coronado had found no mines of gold and silver, and the indigenous population was too decentralized and too hostile (thanks to Soto and Coronado's tender mercies) for Spain to exploit. The southern Atlantic coast of the continent, however, was very familiar to home-bound Spanish mariners, who generally followed that coast after they left the Gulf of Mexico and picked up the Gulf Stream. In the 1550s King Phillip II of Spain supported the establishment of Spanish outposts in Florida to guard the treasure fleets and provide aid to shipwrecked sailors. In 1565, Spanish officer Pedro Menendez de Aviles finally accepted the king's commission and built a string of settlements on the Florida and South Carolina coast, anchored by the garrison town of Saint Augustine. Menendez didn't think small: he hoped one day to establish Spanish colonies in the Chesapeake Bay region, and so he encouraged Jesuit missionaries to open a mission for the Algonquian Indians living there.

Eight Jesuits did set out for the Chesapeake in 1570, accompanied by an Indian translator who was very familiar with the area and its native population. This man, the son of an Algonquian chief, had been captured by Spanish sailors in present-day Virginia in 1561. The mariners had brought him to Mexico City, where he learned Spanish, became a Christian, and adopted the name of his godfather, Viceroy Luis de Velasco. On at least two occasions during the next five years, Velasco traveled to Spain and was presented to Phillip II. By 1570 he was one of the most well-connected people in Spanish Florida, and not surprisingly the Jesuits named their new home on Virginia's York River after him: "Don Luis's Land." (David Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America [Yale, 1992], 64-71.)

Unfortunately for the Jesuits, they established their mission during a time of prolonged famine, and the Algonquians declined to provide them with food. Moreover, "Don Luis" soon abandoned the missionaries and moved to a Native American village, where he proceeded to marry several women and live like the chief's son that he actually was. Facing mounting criticism and hostility from the Jesuits, Velasco soon decided to terminate their mission with extreme prejudice. In early 1571 he organized a war party which killed the eight missionaries and burned their chapel. (ibid, 71-72.)

Nor was that Luis de Velasco's last act of defiance toward Europeans. He later took the name Opechancanough, "He whose soul is white," and became an adviser to his brother, paramount chief Powhatan. When Powhatan died in 1617, Opechancanough became the military leader of Powhatan's confederacy, and in 1622 organized the military strike that killed over 300 English colonists and nearly destroyed the colony of Virginia. Opechancanough somehow survived the bloody ten-year war that followed, and was reportedly around 100 years old when, in 1646, an English settler finally shot him in the back near Jamestown. So ended the life of one of the first inhabitants of Virginia to have visited Europe.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

From the sixteenth-century Spanish viewpoint, North America was a backwater. Explorers like De Soto and Coronado had found no mines of gold and silver, and the indigenous population was too decentralized and too hostile (thanks to Soto and Coronado's tender mercies) for Spain to exploit. The southern Atlantic coast of the continent, however, was very familiar to home-bound Spanish mariners, who generally followed that coast after they left the Gulf of Mexico and picked up the Gulf Stream. In the 1550s King Phillip II of Spain supported the establishment of Spanish outposts in Florida to guard the treasure fleets and provide aid to shipwrecked sailors. In 1565, Spanish officer Pedro Menendez de Aviles finally accepted the king's commission and built a string of settlements on the Florida and South Carolina coast, anchored by the garrison town of Saint Augustine. Menendez didn't think small: he hoped one day to establish Spanish colonies in the Chesapeake Bay region, and so he encouraged Jesuit missionaries to open a mission for the Algonquian Indians living there.

Eight Jesuits did set out for the Chesapeake in 1570, accompanied by an Indian translator who was very familiar with the area and its native population. This man, the son of an Algonquian chief, had been captured by Spanish sailors in present-day Virginia in 1561. The mariners had brought him to Mexico City, where he learned Spanish, became a Christian, and adopted the name of his godfather, Viceroy Luis de Velasco. On at least two occasions during the next five years, Velasco traveled to Spain and was presented to Phillip II. By 1570 he was one of the most well-connected people in Spanish Florida, and not surprisingly the Jesuits named their new home on Virginia's York River after him: "Don Luis's Land." (David Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America [Yale, 1992], 64-71.)

Unfortunately for the Jesuits, they established their mission during a time of prolonged famine, and the Algonquians declined to provide them with food. Moreover, "Don Luis" soon abandoned the missionaries and moved to a Native American village, where he proceeded to marry several women and live like the chief's son that he actually was. Facing mounting criticism and hostility from the Jesuits, Velasco soon decided to terminate their mission with extreme prejudice. In early 1571 he organized a war party which killed the eight missionaries and burned their chapel. (ibid, 71-72.)

Nor was that Luis de Velasco's last act of defiance toward Europeans. He later took the name Opechancanough, "He whose soul is white," and became an adviser to his brother, paramount chief Powhatan. When Powhatan died in 1617, Opechancanough became the military leader of Powhatan's confederacy, and in 1622 organized the military strike that killed over 300 English colonists and nearly destroyed the colony of Virginia. Opechancanough somehow survived the bloody ten-year war that followed, and was reportedly around 100 years old when, in 1646, an English settler finally shot him in the back near Jamestown. So ended the life of one of the first inhabitants of Virginia to have visited Europe.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

The End of History

In addition to other important historical anniversaries (Happy Birthday, Mom!), today is the 200th anniversary of the battles of Jena and Auerstadt, at which Napoleon's Grande Armee (particularly its cavalry) destroyed the Prussian army and drove Prussia out of the Third Coalition. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel later described the battles as "The End of History," which should warn all of us not to read too much into current events.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Arresting the Lollypop Guild

Many adjectives can be used to describe the American misadventure in Iraq, but "funny" has never really been one of them. Military occupation and counter-insurgency don't lend themselves to humor. There are always exceptional moments, however, like the one described by an anonymous Marine in this unclassified September 14th letter:

"[My] Most Surreal Moment [in Iraq] - Watching Marines arrive at my detention facility and unload a truck load of flex-cuffed midgets. 26 to be exact. I had put the word out earlier in the day to the Marines in Fallujah that we were looking for Bad Guy X, who was described as a midget. Little did I know that Fallujah was home to a small community of midgets, who banded together for support since they were considered as social outcasts. The Marines were anxious to get back to the midget colony to bring in the rest of the midget suspects, but I called off the search, figuring Bad Guy X was long gone on his short legs after seeing his companions rounded up by the giant infidels."

The letter deserves to be read in full -- it's a great primary source, filled with telling details ("Favorite Iraqi TV Show - Oprah. I have no idea. They all have satellite TV") and laced with dry wit. One hopes that the author makes it home safely.

"[My] Most Surreal Moment [in Iraq] - Watching Marines arrive at my detention facility and unload a truck load of flex-cuffed midgets. 26 to be exact. I had put the word out earlier in the day to the Marines in Fallujah that we were looking for Bad Guy X, who was described as a midget. Little did I know that Fallujah was home to a small community of midgets, who banded together for support since they were considered as social outcasts. The Marines were anxious to get back to the midget colony to bring in the rest of the midget suspects, but I called off the search, figuring Bad Guy X was long gone on his short legs after seeing his companions rounded up by the giant infidels."

The letter deserves to be read in full -- it's a great primary source, filled with telling details ("Favorite Iraqi TV Show - Oprah. I have no idea. They all have satellite TV") and laced with dry wit. One hopes that the author makes it home safely.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

The Cows, and Coming Home

This week (Saturday the 23rd) marks the 200th anniversary of the return of the Lewis & Clark expedition. Earlier in the month the Corps of Discovery passed several traders' pirogues heading up the Missouri River, but on September 20th, 1806 -- two centuries ago today -- they encountered their first definite sign of European settlement in two years: cattle. "We saw some cows on the bank," William Clark reported, "which was a joyful sight to the party and caused a shout to be raised for joy." (William Bakeless, The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 382.)

It may seem a comical episode, but it also helps affirm Alfred Crosby's observation that the most important feature of early modern European expansion was the "portmanteau biota" Europeans brought with them: cattle, sheep, horses, swine, rabbits, wheat, grapes, peaches, various weed species, and epidemic diseases like smallpox. These plants, animals, and microbes provided European colonists with larger and more reliable supplies of food, fiber, and animal energy than their indigenous competitors, not to mention a biological arsenal (however inadvertantly used) that was far more lethal than Europeans' muskets and artillery. William Clark didn't mention all this in his journal entry, of course, but he did suggest that the most characteristic sound of Euro-American civilization in 1806 was not the pealing of church bells or the clanking of steam engines, but rather the mooing of American settlers' bovine vanguard.

It may seem a comical episode, but it also helps affirm Alfred Crosby's observation that the most important feature of early modern European expansion was the "portmanteau biota" Europeans brought with them: cattle, sheep, horses, swine, rabbits, wheat, grapes, peaches, various weed species, and epidemic diseases like smallpox. These plants, animals, and microbes provided European colonists with larger and more reliable supplies of food, fiber, and animal energy than their indigenous competitors, not to mention a biological arsenal (however inadvertantly used) that was far more lethal than Europeans' muskets and artillery. William Clark didn't mention all this in his journal entry, of course, but he did suggest that the most characteristic sound of Euro-American civilization in 1806 was not the pealing of church bells or the clanking of steam engines, but rather the mooing of American settlers' bovine vanguard.

Monday, September 18, 2006

The Latest Craze with All the Kids Today

In last week's post I mentioned that one of the Inuit who sojourned in Europe in the 1560s had facial tattoos, which were quite common among 16th-century Eskimo men and women. Such tattoos fell out of fashion by the early 20th century, but appear to be making a partial comeback, according to a story in the September 17, 2006 issue of the Anchorage Daily News. Author Alex Demarban reports that several women from the Inupiat community of Barrow, Alaska are reviving the practice of tattooing their chins (usually with blue stripes or circular patterns of dots), as a way of honoring their ancestors and cultural heritage. One man, a whaler, is planning to tattoo a whale-tail necklace on his chest to record his kills.

"Tattoos were common throughout Alaska for hundreds of years," Demarban reports. "Some elder seamstresses used bird-bone needles...sinew, thread, and soot to decorate human canvasses, said Lars Krutak, an anthropologist who studied the custom in Alaska and elsewhere. For women who bore elaborate designs across faces and necks to enhance beauty or fertility, it was a painful rite of passage...For hunters, the etchings - usually dark blue - boosted bravery and could ward off evil spirits."

According to Demarban and Krutak, Christian missionaries and boarding schools were responsible for "stamping out" Inuit facial and chest tattoos, though the indigenous inhabitants of St. Lawrence Island continued the practice into the 1920s. It remains to be seen whether the current revival of facial tattoos is just a quirky decision by a few isolated people, or whether it becomes a larger cultural trend. If the latter is the case, we will at last be able to use the words "major cultural trend" and "Barrow, Alaska" in the same sentence.

"Tattoos were common throughout Alaska for hundreds of years," Demarban reports. "Some elder seamstresses used bird-bone needles...sinew, thread, and soot to decorate human canvasses, said Lars Krutak, an anthropologist who studied the custom in Alaska and elsewhere. For women who bore elaborate designs across faces and necks to enhance beauty or fertility, it was a painful rite of passage...For hunters, the etchings - usually dark blue - boosted bravery and could ward off evil spirits."

According to Demarban and Krutak, Christian missionaries and boarding schools were responsible for "stamping out" Inuit facial and chest tattoos, though the indigenous inhabitants of St. Lawrence Island continued the practice into the 1920s. It remains to be seen whether the current revival of facial tattoos is just a quirky decision by a few isolated people, or whether it becomes a larger cultural trend. If the latter is the case, we will at last be able to use the words "major cultural trend" and "Barrow, Alaska" in the same sentence.

Monday, September 11, 2006

New Prey: Voyagers to the East Part IX (redux)

For the previous entry in this series, click here. For the original Part IX, click here.

In their essay "This New Prey: Eskimos in Europe in 1567, 1576, and 1577" (in Christian Feest, ed., Indians and Europe: An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays [Nebraska, 1999], 61-140), William Sturtevant and David Quinn provide some additional information on these involuntary travelers. The Inuit who came to Europe in 1567 were a woman and her 7-year-old daughter, captured by French or Basque sailors in Labrador the previous year, and put on display in Antwerp and the Hague. A contemporary woodcut portrays the two captives wearing hooded sealskin parkas and shows the unidentified woman's facial tattoos; a German handbill describes them as "wild people and man-eaters" and expresses the hope that mother and daughter were both converted to Christianity (130-131). Sturtevant and Quinn assert, however, that "they cannot have survived long and certainly never saw their homeland again" (68).

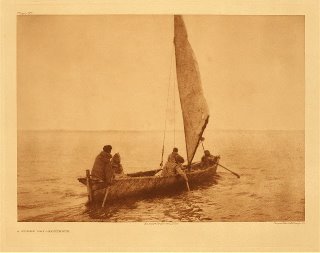

It's a fair guess, because none of the four Inuit whom Frobisher took to England in 1576 and '77 survived for more than a few weeks. The unnamed Inuit man captured in 1576 caught cold while at sea and "died about 15 days after arriving in London" (72). Frobisher and his partners bought medicine and bedding for the man, and paid for his coffin and burial in Saint Olave churchyard, at a total cost of 8 pounds sterling. The three Inuit captured in 1577 -- a man named Kalicho, a woman named Arnaq, and a baby named Nutaaq -- lived only slightly longer. Kalicho was well enough to display his canoeing and duck-hunting skills on the Avon River in October 1577, but he soon sickened and died, probably of an infected lung. Arnaq and Nutaaq died of unspecified causes in early November. Kalicho and Arnaq were interred at St. Stephen's Church in Bristol and Nutaaq at Saint Olave Church in London. (84).

For the next entry in this series, click here.

In their essay "This New Prey: Eskimos in Europe in 1567, 1576, and 1577" (in Christian Feest, ed., Indians and Europe: An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays [Nebraska, 1999], 61-140), William Sturtevant and David Quinn provide some additional information on these involuntary travelers. The Inuit who came to Europe in 1567 were a woman and her 7-year-old daughter, captured by French or Basque sailors in Labrador the previous year, and put on display in Antwerp and the Hague. A contemporary woodcut portrays the two captives wearing hooded sealskin parkas and shows the unidentified woman's facial tattoos; a German handbill describes them as "wild people and man-eaters" and expresses the hope that mother and daughter were both converted to Christianity (130-131). Sturtevant and Quinn assert, however, that "they cannot have survived long and certainly never saw their homeland again" (68).

It's a fair guess, because none of the four Inuit whom Frobisher took to England in 1576 and '77 survived for more than a few weeks. The unnamed Inuit man captured in 1576 caught cold while at sea and "died about 15 days after arriving in London" (72). Frobisher and his partners bought medicine and bedding for the man, and paid for his coffin and burial in Saint Olave churchyard, at a total cost of 8 pounds sterling. The three Inuit captured in 1577 -- a man named Kalicho, a woman named Arnaq, and a baby named Nutaaq -- lived only slightly longer. Kalicho was well enough to display his canoeing and duck-hunting skills on the Avon River in October 1577, but he soon sickened and died, probably of an infected lung. Arnaq and Nutaaq died of unspecified causes in early November. Kalicho and Arnaq were interred at St. Stephen's Church in Bristol and Nutaaq at Saint Olave Church in London. (84).

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Plus ca Change...

While reading Georges Lefebvre's 1939 history of The Coming of the French Revolution , I was struck by the uncanny similarities between the French monarchy's fiscal crisis -- the same crisis that destroyed Louis XVI's government -- and the financial problems of the modern United States government. The Bourbons ran regular budget deficits for most of the 18th century, and by 1788 the annual French deficit had grown to one-fifth of the size of total government outlays. Lefebvre quotes a 1788 budget forecast projecting public expenditures of 629 million livres and revenues of 503 million livres, resulting in a nominal deficit of 126 million livres. The actual deficit, however, was ultimately higher because a poor harvest throttled tax revenues.

Meanwhile, decades of borrowing had created a mammoth national debt and interest payments that crowded out other forms of public spending. In 1788 the French government spent 25% of its money on royal and civil expenses, another 25% on its army and navy -- and a crippling 50% on debt service. France's creditors had reached the end of their patience and would no longer loan money without huge concessions: the national Bank of Discount, for instance, only agreed to float a 100-million-livre loan if the King allowed its notes to circulate as legal tender. (Lefebvre, pp. 21-22)

The regime could not raise existing taxes to cover the shortfall because the commoners, who paid most taxes, had no more money to give. Between 1741 and 1785 "prices had risen 65 per cent and wages only 22 per cent" (p. 23); meanwhile, rents rose by 98%. As in the modern United States, the earnings of ordinary workers -- laborers and tenant farmers, in this case -- were stagnating or declining relative to inflation, while a few landlords and merchants were getting quite rich. Moreover, the wealthiest Frenchmen -- bishops, aristocrats, and rich bourgeois -- were partially or totally exempt from paying taxes. Sound familiar?

The French monarchy had only two ways out of its bind: it could inflate its debt out of existence, which in practice it was beginning to do (by monetizing the Bank of Discount's notes), or require the privileged orders to pay their fair share of taxes. When the King and his councillors chose the latter course, they caused the Breton nobility to rise in rebellion, and other nobles and jurists to demand the calling of the Estates-General, a concession which Louis XVI finally granted and which led to the end of the Old Regime.

The early 21st-century United States hasn't reached the same crisis point, but the comparable data are not reassuring. In FY 2006 U.S. tax receipts equalled $2.18 trillion, over 80% of which came from income and FICA taxes, while outlays equalled $2.57 trillion. 11% of last year's outlays ($390 billion) were financed with deficit spending. Interest payments on the national debt ($210 billion) equalled 8.2% of federal expenditures -- well below the French level, but greater than annual federal spending on Medicaid or combined annual federal spending on education, the environment, and foreign aid, and close to half of the United States' current defense spending (17%).* Finally, median household income in the United States has been stagnant since 1973 and has dropped an average of 2.8% since 2000, while prices have risen 17.5% during the past six years and 365% since 1973. (Sources: Concord Coalition, Washington Monthly [citing U.S. Census Bureau figures], Inflation Calculator.)

Is the United States on the verge of its own Bastille Day? Not exactly -- but we've been headed in that direction for thirty years (the late 1990s excepted), and some of our leaders seem determined to speed up the parade.

* The largest federal expenditures remain Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, which collectively account for 45% of the budget; Paul Krugman isn't exaggerating when he calls the U.S. government "a mammoth insurance company with an incorporated army."

Labels:

Eighteenth Century,

French Revolution,

Politics

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Voyagers to the East: A Preliminary Head Count

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

How many Native Americans visited Europe, willingly or unwillingly, during the first few centuries of European contact? My essay series on these early voyagers is far from complete, but the first nine entries provide enough information to support a preliminary headcount and some early observations.

1493: 17 Tainos brought to Spain by Columbus

1494: (See below)

1495: 350 Tainos and Caribs brought to Spain as slaves

1496: 30 more Tainos taken by Columbus

1501: 50 Micmacs, brought to Portugal as slaves by the Corte-Real expedition

1502: 3 Micmacs (or Inuit) brought to England by Fernandes and Gonsalves

1508: 7 Micmacs brought to France by Aubert

1523: 1 Florida Indian (Francisco de Chicora) brought to Spain

1524: 1 southern Algonquian boy brought to France by Verrazzano

1525: 58 Penobscots taken to Spain as slaves by Gomez

1531: 1 Brazilian chief taken to England by Hawkins

1535-36: 3 Hurons (Donnaconna et al.) brought to France by Cartier

1550: 50 Tupi-Guarani brought to France

1567-77: 5-8 Inuit brought to France and England

In my earlier posts on Columbus I failed to note that the explorer sent over two dozen Carib and Taino captives back to Spain in 1494. Giovanni de'Bardi wrote that several Spanish caravels had returned from the West Indies carrying spices, gold, sandalwood, and "twenty-six Indians of diverse islands and languages." ("Letter from Seville," 19 April 1494, in Geoffrey Symcox and Blair Sullivan, Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies [Boston: St. Martin's, 2005], p. 100.) Adding these 26 men and women to those listed above makes a total of 603-605 Native Americans brought to western Europe between 1493 and 1577.

Of these about 420, or 70%, were Tainos and Caribs brought to Spain by Columbus and his associates between 1493 and 1496. Another 130 were Inuit or Indians from the northeastern edge of North America (Micmacs, Penobscots, and Hurons). Nearly all of the rest were Tupi-Guarani villagers from Brazil. Apart from the aforementioned Hurons, none came from the North American interior.

At least 460 (75%) of these travelers were kidnapped o Spain and Portugal and sold as slaves. The rest accompanied European explorers as trophies, translators, or living advertisements for colonization (as with the 50 Tupi-Guaranis displayed at Rouen in 1550). We may speculate that as Europeans stopped bringing Indians to Europe as slaves -- due to legal prohibitions and the greater demand for slave labor in the Caribbean -- the total number of Indians brought to Europe in the late 16th and 17th centuries also fell. Forthcoming entries in this series will determine whether or not this is an accurate guess.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

How many Native Americans visited Europe, willingly or unwillingly, during the first few centuries of European contact? My essay series on these early voyagers is far from complete, but the first nine entries provide enough information to support a preliminary headcount and some early observations.

1493: 17 Tainos brought to Spain by Columbus

1494: (See below)

1495: 350 Tainos and Caribs brought to Spain as slaves

1496: 30 more Tainos taken by Columbus

1501: 50 Micmacs, brought to Portugal as slaves by the Corte-Real expedition

1502: 3 Micmacs (or Inuit) brought to England by Fernandes and Gonsalves

1508: 7 Micmacs brought to France by Aubert

1523: 1 Florida Indian (Francisco de Chicora) brought to Spain

1524: 1 southern Algonquian boy brought to France by Verrazzano

1525: 58 Penobscots taken to Spain as slaves by Gomez

1531: 1 Brazilian chief taken to England by Hawkins

1535-36: 3 Hurons (Donnaconna et al.) brought to France by Cartier

1550: 50 Tupi-Guarani brought to France

1567-77: 5-8 Inuit brought to France and England

In my earlier posts on Columbus I failed to note that the explorer sent over two dozen Carib and Taino captives back to Spain in 1494. Giovanni de'Bardi wrote that several Spanish caravels had returned from the West Indies carrying spices, gold, sandalwood, and "twenty-six Indians of diverse islands and languages." ("Letter from Seville," 19 April 1494, in Geoffrey Symcox and Blair Sullivan, Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies [Boston: St. Martin's, 2005], p. 100.) Adding these 26 men and women to those listed above makes a total of 603-605 Native Americans brought to western Europe between 1493 and 1577.

Of these about 420, or 70%, were Tainos and Caribs brought to Spain by Columbus and his associates between 1493 and 1496. Another 130 were Inuit or Indians from the northeastern edge of North America (Micmacs, Penobscots, and Hurons). Nearly all of the rest were Tupi-Guarani villagers from Brazil. Apart from the aforementioned Hurons, none came from the North American interior.

At least 460 (75%) of these travelers were kidnapped o Spain and Portugal and sold as slaves. The rest accompanied European explorers as trophies, translators, or living advertisements for colonization (as with the 50 Tupi-Guaranis displayed at Rouen in 1550). We may speculate that as Europeans stopped bringing Indians to Europe as slaves -- due to legal prohibitions and the greater demand for slave labor in the Caribbean -- the total number of Indians brought to Europe in the late 16th and 17th centuries also fell. Forthcoming entries in this series will determine whether or not this is an accurate guess.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Voyagers to the East, Part IX

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

As educated Europeans' interest in the New World and its inhabitants continued to grow, mariners continued to bring captive Native Americans to Europe, either to help promote colonial ventures or as money-making exhibits in their own right. During the second half of the 1500s, several navigators succeeded in accomplishing what Thomas Hore and his colleagues had failed to do in the 1530s: capturing Inuit men and women and returning with them to Europe. In 1567 French or Flemish sailors brought several Eskimo captives back to the Continent, and in 1576-77 the English explorer Martin Frobisher captured four Inuit -- two men, a woman and a baby -- during two separate voyages along the coast of Baffin Island. Frobisher was searching for a Northwest Passage to China, but during his reconnaissance he discovered what he believed to be rich gold deposits, and he brought his hostages back to England to build support for a mining colony in far northern North America. Frobisher's colony in "Meta Incognita" (as Queen Elizabeth I called it) died quickly, once the "gold" deposits turned out to be iron pyrite, and his Inuit captives almost certainly died within a few months of reaching England -- though they apparently lived long enough to allow John White to paint their portraits in watercolors. (Goertzman and Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration, 28-29.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

As educated Europeans' interest in the New World and its inhabitants continued to grow, mariners continued to bring captive Native Americans to Europe, either to help promote colonial ventures or as money-making exhibits in their own right. During the second half of the 1500s, several navigators succeeded in accomplishing what Thomas Hore and his colleagues had failed to do in the 1530s: capturing Inuit men and women and returning with them to Europe. In 1567 French or Flemish sailors brought several Eskimo captives back to the Continent, and in 1576-77 the English explorer Martin Frobisher captured four Inuit -- two men, a woman and a baby -- during two separate voyages along the coast of Baffin Island. Frobisher was searching for a Northwest Passage to China, but during his reconnaissance he discovered what he believed to be rich gold deposits, and he brought his hostages back to England to build support for a mining colony in far northern North America. Frobisher's colony in "Meta Incognita" (as Queen Elizabeth I called it) died quickly, once the "gold" deposits turned out to be iron pyrite, and his Inuit captives almost certainly died within a few months of reaching England -- though they apparently lived long enough to allow John White to paint their portraits in watercolors. (Goertzman and Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration, 28-29.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Sunday, July 16, 2006

Target-Rich Environment

Several weeks ago, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security caused considerable alarm by announcing substantial cuts in anti-terrorism funding for major American cities, and by declaring that there were no significant terrorist targets in New York City. Now, thanks to an internal audit of the department's National Asset Database (detailed in The Carpetbagger Report), we know what the DHS considers likely targets for terrorist attack:

* Old MacDonald's Petting Zoo (Huntsville, AL)

* The Amish Country Popcorn factory (Berne, IN)

* Kangaroo Conservation Center (Dawsonville, GA)

* Bourbon Festival (Bardstown, KY)

* The Mule Day Parade (Columbia, TN)

* The Sweetwater Flea Market (Sweetwater, TN)

* Bean Fest (Mountain View, AR)

* Nix's Check Cashing

* Mall at Sears

* Ice Cream Parlor

* Donut Shop

Most of these strategic installations are in Midwestern and Southern states whose voters have been more supportive of the current presidential administration than New Yorkers. In fact, the state with the longest list of potential targets is Indiana, which has voted Republican in every presidential election since 1964, and whose current governor used to direct George W. Bush's Office of Management and Budget. Indiana's homeland security department identified 8,500 vital assets in need of federal protection -- nearly as many as California and New York combined. (Last Thursday the Indiana DHS claimed that they were "confused." No doubt.)

It's tempting to argue that this list demonstrates the incompetence of the Homeland Security Dept. It's equally tempting to speculate that our Protectors of the Homeland have concluded, after reading several Philip K. Dick novels (Time Out of Joint in particular), that such seemingly mundane places as "Tackle Shop" and "Beach at End of a Street" are actually of vital importance to national security. Homeland Security Inspector General Richard Skinner, whose audit of the National Asset Database led to this story, doesn't seem to agree that the database is "an accurate representation of the nation's...critical infrastructure and key resources," but perhaps he just can't perceive the hidden truths to which his more illuminated colleagues are privy.

* Old MacDonald's Petting Zoo (Huntsville, AL)

* The Amish Country Popcorn factory (Berne, IN)

* Kangaroo Conservation Center (Dawsonville, GA)

* Bourbon Festival (Bardstown, KY)

* The Mule Day Parade (Columbia, TN)

* The Sweetwater Flea Market (Sweetwater, TN)

* Bean Fest (Mountain View, AR)

* Nix's Check Cashing

* Mall at Sears

* Ice Cream Parlor

* Donut Shop

Most of these strategic installations are in Midwestern and Southern states whose voters have been more supportive of the current presidential administration than New Yorkers. In fact, the state with the longest list of potential targets is Indiana, which has voted Republican in every presidential election since 1964, and whose current governor used to direct George W. Bush's Office of Management and Budget. Indiana's homeland security department identified 8,500 vital assets in need of federal protection -- nearly as many as California and New York combined. (Last Thursday the Indiana DHS claimed that they were "confused." No doubt.)

It's tempting to argue that this list demonstrates the incompetence of the Homeland Security Dept. It's equally tempting to speculate that our Protectors of the Homeland have concluded, after reading several Philip K. Dick novels (Time Out of Joint in particular), that such seemingly mundane places as "Tackle Shop" and "Beach at End of a Street" are actually of vital importance to national security. Homeland Security Inspector General Richard Skinner, whose audit of the National Asset Database led to this story, doesn't seem to agree that the database is "an accurate representation of the nation's...critical infrastructure and key resources," but perhaps he just can't perceive the hidden truths to which his more illuminated colleagues are privy.

Friday, July 07, 2006

No Land War in Asia

Apropos of the United States' current round of mutual saber-rattling with North Korea, and for the edification of those who may feel that Kim Jong Il's pursuit of nuclear weapons and long-range missiles makes him more of an international threat than Saddam Hussein once was, I offer the following corrective primer, courtesy of my friend and Far Eastern Affairs consultant, Jon Lay:

TOP TEN REASONS TO REACT DIFFERENTLY TO NORTH KOREA IN 2006 THAN WE DID TO IRAQ IN 2003:

10) They actually have Weapons of Mass Destruction. You know what those do, right?

9) Restarting the Cold War will significantly diminish the value of Reagan Dimes.

8) Japan is asking us to intervene, and frankly, we're feeling like we've been doing a lot for Japan over the last 60 years.

7) Not threatening to invade them just because they're not Arabs, would – in its own way – also be racist, if you think about it. No, think about it some more. More. There you go.

6) The United States has no idea how to go about waging a war on the Korean Peninsula.

5) Toby Keith still negotiating soundtrack terms. Once we get that worked out, it's bombs away.

4) Disrupting the flow of cheap plastic crap from China is potentially more damaging to our economy than losing whatever it is that we import from the Middle East.

3) George Bush is a pacifist firmly committed to resolving all conflicts through dialogue, as Jesus would.

2) With Army enlistment and morale at such record heights, we're worried we'd beat them so badly other nations would feel bad about themselves.

1) Osama Bin Laden didn't tell us to get the hell out of South Korea like he did Saudi Arabia – so we don't need to move our troops to North Korea.

TOP TEN REASONS TO REACT DIFFERENTLY TO NORTH KOREA IN 2006 THAN WE DID TO IRAQ IN 2003:

10) They actually have Weapons of Mass Destruction. You know what those do, right?

9) Restarting the Cold War will significantly diminish the value of Reagan Dimes.

8) Japan is asking us to intervene, and frankly, we're feeling like we've been doing a lot for Japan over the last 60 years.

7) Not threatening to invade them just because they're not Arabs, would – in its own way – also be racist, if you think about it. No, think about it some more. More. There you go.

6) The United States has no idea how to go about waging a war on the Korean Peninsula.

5) Toby Keith still negotiating soundtrack terms. Once we get that worked out, it's bombs away.

4) Disrupting the flow of cheap plastic crap from China is potentially more damaging to our economy than losing whatever it is that we import from the Middle East.

3) George Bush is a pacifist firmly committed to resolving all conflicts through dialogue, as Jesus would.

2) With Army enlistment and morale at such record heights, we're worried we'd beat them so badly other nations would feel bad about themselves.

1) Osama Bin Laden didn't tell us to get the hell out of South Korea like he did Saudi Arabia – so we don't need to move our troops to North Korea.

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Voyagers to the East, Part VIII

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

A noteworthy feature of 16th-century French political culture was the ceremonial entry of a new king into each of the principal cities of his realm. These "joyeuses entrees" were festive events marked by parades, pageants, feasts, public addresses, and (usually) the city's presentation of a large gift to the king. The festival of entry satisfied the king's need for homage, but it also served two important purposes for the local citizens: it allowed them to re-affirm their special corporate identity as city-dwellers, and it gave them the opportunity to express their community's aspirations. (Frederic Baumgartner, Henry II: King of France, 1547-1559 [Duke University Press, 1988], 92-93.)

In October 1550 the city fathers of Rouen, a maritime community on the Seine estuary, organized an unusual entry festival for King Henri II and Catherine de Medici, one intended to promote royal interest in overseas colonization. In a field outside of the city walls the inhabitants prepared a simulated Brazilian forest and village, complete with fake brazilwood trees, imported parrots and monkeys, log huts with thatched roofs, hammocks, and dugout canoes. The tableau included over three hundred "Brazilians," who paraded before the monarchs and conducted a mock battle with bows and clubs.

Fifty of these tribesmen were actual Brazilians, probably Tupi-Guarani kidnapped by Portuguese slavers and sold to sailors involved in the lumber trade. (Brazil's primary export in the early 16th century was brazilwood, which Europeans used as a dyestuff.) Some of the other 250 participants were French sailors familiar with the Brazilian coast, its inhabitants, and their language. Most were ordinary young French men and women dressed, or rather undressed, as Indians, wearing little more than a coating of red dye. (This must have been chilly in early October). The pageant thus represents one of the earliest recorded examples of a cultural activity that would, in time, become quite popular in British America: "playing Indian."

Rouen's merchants and sailors hoped that the pageant would build political support for trade with the Indies and colonization in America, and their hopes were soon realized. In 1555 Henri II commissioned a party of adventurers to establish a French colony in southern Brazil, near the site of present-day Rio de Janeiro. The settlement of "France Antarctique" survived for twelve years, and descriptions of its Native American neighbors inspired Michel de Montaigne to write his essay "Of Cannibals," an early exploration of the theme of the "noble savage." (Parts of his theme found their way into Act II, Scene 1 of The Tempest). It seems possible that some of the kidnapped Tupi-Guaranis who participated in the 1550 pageant came to the new colony as guides and translators, though there is no certain documentary proof of their fate.

A contemporary description of the Brazilian pageant, titled La deduction du sumpteux order plaisantz spectacles et magnifiques theatres dresses ... par les citoiens de Rouen ... a la sacrée maieste du treschristian roy de France, Henry seco[n]d ... et à tresillustre dame, ma dame Katharine de Medicis [Rouen, 1551], p. 67, can be found here on the British Library website. A 2006 book on the pageant, Michael Wintroub's A Savage Mirror, is available from Stanford University Press.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

A noteworthy feature of 16th-century French political culture was the ceremonial entry of a new king into each of the principal cities of his realm. These "joyeuses entrees" were festive events marked by parades, pageants, feasts, public addresses, and (usually) the city's presentation of a large gift to the king. The festival of entry satisfied the king's need for homage, but it also served two important purposes for the local citizens: it allowed them to re-affirm their special corporate identity as city-dwellers, and it gave them the opportunity to express their community's aspirations. (Frederic Baumgartner, Henry II: King of France, 1547-1559 [Duke University Press, 1988], 92-93.)

In October 1550 the city fathers of Rouen, a maritime community on the Seine estuary, organized an unusual entry festival for King Henri II and Catherine de Medici, one intended to promote royal interest in overseas colonization. In a field outside of the city walls the inhabitants prepared a simulated Brazilian forest and village, complete with fake brazilwood trees, imported parrots and monkeys, log huts with thatched roofs, hammocks, and dugout canoes. The tableau included over three hundred "Brazilians," who paraded before the monarchs and conducted a mock battle with bows and clubs.

Fifty of these tribesmen were actual Brazilians, probably Tupi-Guarani kidnapped by Portuguese slavers and sold to sailors involved in the lumber trade. (Brazil's primary export in the early 16th century was brazilwood, which Europeans used as a dyestuff.) Some of the other 250 participants were French sailors familiar with the Brazilian coast, its inhabitants, and their language. Most were ordinary young French men and women dressed, or rather undressed, as Indians, wearing little more than a coating of red dye. (This must have been chilly in early October). The pageant thus represents one of the earliest recorded examples of a cultural activity that would, in time, become quite popular in British America: "playing Indian."

Rouen's merchants and sailors hoped that the pageant would build political support for trade with the Indies and colonization in America, and their hopes were soon realized. In 1555 Henri II commissioned a party of adventurers to establish a French colony in southern Brazil, near the site of present-day Rio de Janeiro. The settlement of "France Antarctique" survived for twelve years, and descriptions of its Native American neighbors inspired Michel de Montaigne to write his essay "Of Cannibals," an early exploration of the theme of the "noble savage." (Parts of his theme found their way into Act II, Scene 1 of The Tempest). It seems possible that some of the kidnapped Tupi-Guaranis who participated in the 1550 pageant came to the new colony as guides and translators, though there is no certain documentary proof of their fate.

A contemporary description of the Brazilian pageant, titled La deduction du sumpteux order plaisantz spectacles et magnifiques theatres dresses ... par les citoiens de Rouen ... a la sacrée maieste du treschristian roy de France, Henry seco[n]d ... et à tresillustre dame, ma dame Katharine de Medicis [Rouen, 1551], p. 67, can be found here on the British Library website. A 2006 book on the pageant, Michael Wintroub's A Savage Mirror, is available from Stanford University Press.

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Saturday, June 17, 2006

Shocked, I Say

Occasionally, I come across a newspaper story so entertaining that it merits retelling without comment. The June 9th issue of the Chronicle of Higher Education carried such a story (page A25), from which comes the following excerpt: "The University of Missouri at Columbia is having a difficult time making use of a $1.1 million donation that Kenneth L. Lay gave in 1999 to establish the Kenneth L. Lay Chair in Economics." According to the story the university offered the job to three different professors between 2000 and 2003, and all of them declined.

I will afford myself one small comment: a $1.1 million endowment would support a professorship whose annual salary would be around $60,000-70,000, plus benefits. This is only 1/3 to 1/2 of what a senior economics professor normally earns at a flagship research university. It's therefore entirely possible that Missouri can't fill the Lay Chair because its benefactor was too cheap, not because he's infamous. If Mr. Lay had instead donated $11 million, that chair would not have remained vacant for long.

[Update, July 6th: I guess it's now the Kenneth L. Lay Memorial Chair in Economics.]

I will afford myself one small comment: a $1.1 million endowment would support a professorship whose annual salary would be around $60,000-70,000, plus benefits. This is only 1/3 to 1/2 of what a senior economics professor normally earns at a flagship research university. It's therefore entirely possible that Missouri can't fill the Lay Chair because its benefactor was too cheap, not because he's infamous. If Mr. Lay had instead donated $11 million, that chair would not have remained vacant for long.

[Update, July 6th: I guess it's now the Kenneth L. Lay Memorial Chair in Economics.]

Friday, June 09, 2006

Pine Trees and Sovereignty

June 10th marks the anniversary of the issuance of the Pine Tree Shilling (1652), the first coin minted by English-speaking settlers in North America. Those who might regard this as mere numismatic trivia are invited to read Mark Peterson's fascinating essay in the April 2006 issue of Common Place, "Big Money Comes to Boston." In it, Peterson notes the difference between what he calls "big money" (gold and silver coins issued by sovereign states) and "little money" (informal currencies like cowrie shells) in the 17th-century Atlantic world, and identifies the minting of the Pine Tree Shilling as the moment when Bostonians formally shifted to a big-money economy. He also explains how Bostonians' efforts to establish first a little-money economy, based on wampum, and then a big-money economy based on precious metals reflected the colony's ambitious territorial and commercial aspirations, linking coinage to the fur trade, the Pequot War, the silver mines of Potosi, and the West Indies. Finally, he describes the amusing -- and, for a long time, successful -- efforts of colonial officials to convince Charles II that they had not usurped his royal prerogative. (I particularly liked Sir Thomas Temple's insistence that the pine tree engraving was actually the Royal Oak, in which Charles II had hidden after losing the Battle of Worcester [1651], and that the coin was therefore a hidden tribute to the exiled king.) Charles' brother James was not taken in by such arguments and put an end to the new coinage when he became king, but this was merely a temporary setback for New England officials, who in the eighteenth century found a new way to produce money: by printing it.

(Image above is from the National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, via http://amhistory.si.edu/coins/printable/coin.cfm?coincode=1_00. Added 11 June 2018.)

(Image above is from the National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, via http://amhistory.si.edu/coins/printable/coin.cfm?coincode=1_00. Added 11 June 2018.)

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Madisonian Legacies

Several weeks ago there was a scholarly exchange on H-NET (the Humanities Network at Michigan State University) regarding the current obscurity of James Madison. One professor referred to Madison as one of the most "under-appreciated" members of the American Founding generation. Another observed that Madison, who was not only president but also the principal author of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, has no monument in Washington, D.C., appears on no coins or currency (except the long-retired $10,000 bill), and graces no best-selling biographies. Little remains of the fourth president, he remarked, except a small Midwestern state capital, a street in New York City, and a mermaid in an obscure comedy film.

Perhaps Americans have forgotten Madison's political accomplishments, and his presidency too (just as well, since it was a disaster), but we should note that his name has not been forgotten. On May 12th the Social Security Administration released its annual list of popular baby names for 2005, and I was pleased to note that Madison remains one of the most popular names for newborn girls in the United States -- No. 3 on the list, in fact. It has held that position since 2003, and was the second most popular name for baby girls in 2001-02. Why parents would name their female children for a short, neurasthenic male slave-owner from Virginia is something of a mystery, though I suspect it has something to do with the mermaid named Madison (played by Daryl Hannah) from the aforementioned 1984 film Splash. I do know, however, that if Thomas Jefferson were to come back to America twenty years from now, and see how many hundreds of thousands of young women were named for his friend and contemporary, he would be jealous.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Voyagers to the East, Part VII

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

During the first half of the sixteenth century England was a minor maritime power, and few English sailors joined the French and Spanish effort to explore the Americas. One adventurer, though, played a small but significant part in the creation of a trans-Atlantic economy: in the early 1530s William Hawkins of Plymouth (1455-1554) made three voyages to Brazil and West Africa, and introduced the English to Brazilian hardwoods and African ivory. (His son, Admiral Sir John Hawkins, later inaugurated the English slave trade by selling 300 African slaves he had captured from Portuguese traders.) Hawkins returned from his second voyage to Brazil (1531) with a Brazilian "king," who apparently came willingly and became a prized guest at the court of Henry VIII. According to contemporary chroniclers, King Henry's courtiers were particularly impressed with the chief's pierced cheeks and with the great jewel mounted in his "nether lip." Hawkins probably wanted his guest to help inaugurate regular commerce between England and the native peoples of northeastern Brazil, but there's no evidence that the chief learned much English, and in any event he died during the return voyage in 1532. (Alden Vaughan, "Sir Walter Ralegh's Indian Interpreters," William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 59 [April 2002], 344; Giles Milton, Big Chief Elizabeth [New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000], 7-8.)

Hawkins's Brazilian king made such a splash that several Englishmen decided they could make a lot of money by kidnapping other Native Americans and putting them on display in London. In 1535-36 a company of wealthy gentlemen, headed by the merchant Thomas Hore, organized an expedition to America to seize human trophies. The adventurers hired the ships William and Trinity, sailed from London in April 1536, paused in Newfoundland to take on supplies, then sailed up the coast of Labrador in search of "savages." Finally they encountered a small party of Inuit or Beothuk hunters paddling out to meet their ship, but when the Englishmen attempted to capture the Americans their quarry escaped. The explorers later discovered that the Trinity had suffered so much ice damage that it had to be laid up for repairs. While these were underway the Englishmen ran out of food and some resorted to cannibalism.

Finally, Richard Hore and his followers hailed a French fishing vessel, which they managed to seize from its crew, and returned thereon to England. When the English explorers landed in Saint Ives in October 1536, they returned not in triumph but weak, hungry, disgraced, and empty-handed. Their failure chilled Englishmen's interest in exploring the Americas for another quarter-century. (Milton, op. cit., 9-15. See also Richard Hakluyt's account of the voyage, here.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

During the first half of the sixteenth century England was a minor maritime power, and few English sailors joined the French and Spanish effort to explore the Americas. One adventurer, though, played a small but significant part in the creation of a trans-Atlantic economy: in the early 1530s William Hawkins of Plymouth (1455-1554) made three voyages to Brazil and West Africa, and introduced the English to Brazilian hardwoods and African ivory. (His son, Admiral Sir John Hawkins, later inaugurated the English slave trade by selling 300 African slaves he had captured from Portuguese traders.) Hawkins returned from his second voyage to Brazil (1531) with a Brazilian "king," who apparently came willingly and became a prized guest at the court of Henry VIII. According to contemporary chroniclers, King Henry's courtiers were particularly impressed with the chief's pierced cheeks and with the great jewel mounted in his "nether lip." Hawkins probably wanted his guest to help inaugurate regular commerce between England and the native peoples of northeastern Brazil, but there's no evidence that the chief learned much English, and in any event he died during the return voyage in 1532. (Alden Vaughan, "Sir Walter Ralegh's Indian Interpreters," William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 59 [April 2002], 344; Giles Milton, Big Chief Elizabeth [New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000], 7-8.)

Hawkins's Brazilian king made such a splash that several Englishmen decided they could make a lot of money by kidnapping other Native Americans and putting them on display in London. In 1535-36 a company of wealthy gentlemen, headed by the merchant Thomas Hore, organized an expedition to America to seize human trophies. The adventurers hired the ships William and Trinity, sailed from London in April 1536, paused in Newfoundland to take on supplies, then sailed up the coast of Labrador in search of "savages." Finally they encountered a small party of Inuit or Beothuk hunters paddling out to meet their ship, but when the Englishmen attempted to capture the Americans their quarry escaped. The explorers later discovered that the Trinity had suffered so much ice damage that it had to be laid up for repairs. While these were underway the Englishmen ran out of food and some resorted to cannibalism.

Finally, Richard Hore and his followers hailed a French fishing vessel, which they managed to seize from its crew, and returned thereon to England. When the English explorers landed in Saint Ives in October 1536, they returned not in triumph but weak, hungry, disgraced, and empty-handed. Their failure chilled Englishmen's interest in exploring the Americas for another quarter-century. (Milton, op. cit., 9-15. See also Richard Hakluyt's account of the voyage, here.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Friday, May 05, 2006

Voyagers to the East, Part VI

For the previous entry in this series, click here.

A year after Verrazzano completed his reconnaissance of the North American coast, another European explorer, Estevao Gomes -- a Portuguese mariner commanding a Spanish expedition -- retraced part of his route. In 1525 Gomes sailed up the coast of New England and ascended a waterway he called the Rio de Santa Maria, later known as the Penobscot River. At the head of navigation, near present-day Bangor, Gomes and his men encountered a large party of Penobscot Indians, some of whom the explorers enticed aboard their ship and captured. Like his Spanish contemporaries in the West Indies, or like the Corte-Reals a quarter-century earlier, Gomes hoped to make his expedition profitable by enslaving and selling Indians. He made the mistake, however, of bringing his Penobscot captives back to Spain, where royal and noble opinion had turned against Native American slavery.

Fifty-eight Penobscots survived the ocean crossing to La Coruna in the summer of 1525. When Gomes attempted to sell the captives to Spanish merchants, the Crown seized them, baptized them, nominally freed them, and turned them over to royal guardians. Some promoters of Spanish settlement trained three of the captives as translators, in case Spain should wish to colonize present-day Maine, but nothing came of this venture. The rest became their guardians' servants, not quite slaves but certainly not free to find their own employers or leave the country. It is unlikely any ever made it home. (David Quinn, North America, 160-162.)

The Verrazzano and Gomes expeditions proved to Europeans that North America was a large continent that extended continuously from the Tropics to the Arctic Circle. Yet European explorers continued to search for the elusive Northwest Passage, which some believed they could reach via the Strait of Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador. In 1534 the French navigator Jacques Cartier, commanding three ships that carried enough provisions for a trip to China, sailed through the Strait and explored the coasts of western Newfoundland and eastern Labrador. He then crossed to Prince Edward Island and the Gaspe Peninsula, where he met several hundred Micmacs and Hurons who had come to the Bay of Chaleur to fish. Cartier and his men traded with the Indians and captured a Huron chief, Donnaconna, who had come to warn the Frenchmen off; they subsequently released Donnaconna but arranged to take two young Huron men, Domagaya (the chief's son) and Taignoagny, back to France to serve as translators. The explorers and their Indian companions (one might say hostages) returned to St. Malo that September.

By 1535 the two translators had learned enough French to provide Cartier with information about the Saint Lawrence River, which he ascended during his second voyage to America later that year. Domagaya and Taignoagny accompanied Cartier back to Canada on that expedition, during which the Frenchmen discovered and described the Iroquois town of Hochelaga (present-day Montreal), endured a cruel winter on the Saint Charles River, and succeeded in kidnapping Donnaconna and several of his kinsmen. The expeditionaries returned to France in July 1536, accompanied by the chief and the two former translators. (ibid, 169-181.)

Donnaconna remained in France and informed Cartier and the French court that the St. Lawrence Valley was rich in gold and gems, a story that inspired an unsuccessful French attempt to establish a colony in Canada in 1541. The chief himself died sometime between 1536 and 1540, and David Quinn suggests that he was killed by "good living." (181) There was certainly much of that in mid-16th-century France, where wages were high and food was ample; in 1560 a Norman squire reported that "In my father's time, we ate meat every day, dishes were abundant, we gulped down wine as if it were water." (quoted in Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, Volume I: the Structures of Everyday Life [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992], 195.) It is also quite possible, however, that Donnaconna died of disease -- perhaps the plague, which recurred with distressing frequency in 16th-century France. (ibid, 84.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

A year after Verrazzano completed his reconnaissance of the North American coast, another European explorer, Estevao Gomes -- a Portuguese mariner commanding a Spanish expedition -- retraced part of his route. In 1525 Gomes sailed up the coast of New England and ascended a waterway he called the Rio de Santa Maria, later known as the Penobscot River. At the head of navigation, near present-day Bangor, Gomes and his men encountered a large party of Penobscot Indians, some of whom the explorers enticed aboard their ship and captured. Like his Spanish contemporaries in the West Indies, or like the Corte-Reals a quarter-century earlier, Gomes hoped to make his expedition profitable by enslaving and selling Indians. He made the mistake, however, of bringing his Penobscot captives back to Spain, where royal and noble opinion had turned against Native American slavery.

Fifty-eight Penobscots survived the ocean crossing to La Coruna in the summer of 1525. When Gomes attempted to sell the captives to Spanish merchants, the Crown seized them, baptized them, nominally freed them, and turned them over to royal guardians. Some promoters of Spanish settlement trained three of the captives as translators, in case Spain should wish to colonize present-day Maine, but nothing came of this venture. The rest became their guardians' servants, not quite slaves but certainly not free to find their own employers or leave the country. It is unlikely any ever made it home. (David Quinn, North America, 160-162.)

The Verrazzano and Gomes expeditions proved to Europeans that North America was a large continent that extended continuously from the Tropics to the Arctic Circle. Yet European explorers continued to search for the elusive Northwest Passage, which some believed they could reach via the Strait of Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador. In 1534 the French navigator Jacques Cartier, commanding three ships that carried enough provisions for a trip to China, sailed through the Strait and explored the coasts of western Newfoundland and eastern Labrador. He then crossed to Prince Edward Island and the Gaspe Peninsula, where he met several hundred Micmacs and Hurons who had come to the Bay of Chaleur to fish. Cartier and his men traded with the Indians and captured a Huron chief, Donnaconna, who had come to warn the Frenchmen off; they subsequently released Donnaconna but arranged to take two young Huron men, Domagaya (the chief's son) and Taignoagny, back to France to serve as translators. The explorers and their Indian companions (one might say hostages) returned to St. Malo that September.

By 1535 the two translators had learned enough French to provide Cartier with information about the Saint Lawrence River, which he ascended during his second voyage to America later that year. Domagaya and Taignoagny accompanied Cartier back to Canada on that expedition, during which the Frenchmen discovered and described the Iroquois town of Hochelaga (present-day Montreal), endured a cruel winter on the Saint Charles River, and succeeded in kidnapping Donnaconna and several of his kinsmen. The expeditionaries returned to France in July 1536, accompanied by the chief and the two former translators. (ibid, 169-181.)

Donnaconna remained in France and informed Cartier and the French court that the St. Lawrence Valley was rich in gold and gems, a story that inspired an unsuccessful French attempt to establish a colony in Canada in 1541. The chief himself died sometime between 1536 and 1540, and David Quinn suggests that he was killed by "good living." (181) There was certainly much of that in mid-16th-century France, where wages were high and food was ample; in 1560 a Norman squire reported that "In my father's time, we ate meat every day, dishes were abundant, we gulped down wine as if it were water." (quoted in Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, Volume I: the Structures of Everyday Life [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992], 195.) It is also quite possible, however, that Donnaconna died of disease -- perhaps the plague, which recurred with distressing frequency in 16th-century France. (ibid, 84.)

For the next entry in this series, click here.

Labels:

Food Glorious Food,

Indians in Europe,

Penobscots

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

A Stereotypical Ukrainian

In 1945 George Orwell reported that the British Army had recently captured two "German" soldiers whose actual nationality was indeterminable. They were obviously of Asiatic descent, but spoke no language known to their interrogators and could not provide their names or any other information. Finally, a British officer who had spent time in India determined that the captives were, in fact, from Tibet. They had been conscripted by a Chinese warlord in the 1930s, captured by the Soviets during a border skirmish and conscripted into the Red Army, and then captured a third time by the Wehrmacht and sent to France as laborers. Orwell proposed that Britain draft these very untypical German soldiers into the army it was sending to Malaya, then allow them to wander back to Tibet, thus completing their involuntary circumnavigation of the globe.

This story always struck me as the best personal, small-scale example of the disruption inflicted upon every corner of the world by the Second World War. However, another story reported last week by the Associated Press is nearly as good. On April 18th of this year Ishinosuke Uwano, a former Japanese soldier whose relatives had declared him legally dead, surfaced at the Japanese embassy in Kiev. Uwano had been drafted into the Imperial Army in 1943 and sent to Sakhalin Island, north of Hokkaido. In August 1945 the USSR declared war on Japan, and the Red Army swiftly overran the Japanese garrisons on southern Sakhalin Island. Uwano became one of 600,000 Japanese prisoners-of-war whom the USSR did not repatriate after the end of the war; instead, he was kept on Soviet-occupied Sakhalin Island for another thirteen years, most likely as a laborer. At some point thereafter, the former POW became a Soviet citizen, and in 1965 moved to Ukraine, where he learned the language, married, had three children, and became for all practical purposes a Ukrainian.

Last week Uwano, now 83 years old, applied at the Japanese embassy in Ukraine for permission to return to Japan, saying "I would like to visit my parents' graves and to see cherry blossoms." The BBC reported that he flew to Tokyo with his son Anatolii on April 19th and began a ten-day visit to his old home town, where he met his surviving siblings, nieces, and nephews. He apparently does not wish to stay in Japan, viewing himself as a citizen of independent Ukraine; indeed, he has largely forgotten the Japanese language, which he hasn't spoken for 60 years.

The Times of London reminds us that "lost" Japanese World War Two soldiers have turned up in strange places before -- some, trapped at war's end on isolated Pacific islands or in the remoter parts of the Philippines, never learned that the war had ended and lived for years as hermits or guerillas. In some ways, however, the war disturbed Uwano's life far more than theirs. They never had to face the new realities of the postwar world: that Imperial Japan was dead, the hated Communists were triumphant throughout Eurasia, and no-one in the "Free World" cared what the Russians did to a few million German and Japanese prisoners. Ishinosuke Uwano was lucky: the great majority of the POWs conscripted by the Soviets in 1945 wound up in poorly-marked graves in Siberia. Uwano, at least, lived to see the fall of the Soviet Empire, the "Orange Revolution" in Ukraine, and his own homecoming.

Update, 10 June 2018: The Orwell story mentioned at the start of this post actually appeared in 1944, in the author's "As I Please" column. To the best of my knowledge, Ishinosuke Uwano remains alive.

This story always struck me as the best personal, small-scale example of the disruption inflicted upon every corner of the world by the Second World War. However, another story reported last week by the Associated Press is nearly as good. On April 18th of this year Ishinosuke Uwano, a former Japanese soldier whose relatives had declared him legally dead, surfaced at the Japanese embassy in Kiev. Uwano had been drafted into the Imperial Army in 1943 and sent to Sakhalin Island, north of Hokkaido. In August 1945 the USSR declared war on Japan, and the Red Army swiftly overran the Japanese garrisons on southern Sakhalin Island. Uwano became one of 600,000 Japanese prisoners-of-war whom the USSR did not repatriate after the end of the war; instead, he was kept on Soviet-occupied Sakhalin Island for another thirteen years, most likely as a laborer. At some point thereafter, the former POW became a Soviet citizen, and in 1965 moved to Ukraine, where he learned the language, married, had three children, and became for all practical purposes a Ukrainian.

Last week Uwano, now 83 years old, applied at the Japanese embassy in Ukraine for permission to return to Japan, saying "I would like to visit my parents' graves and to see cherry blossoms." The BBC reported that he flew to Tokyo with his son Anatolii on April 19th and began a ten-day visit to his old home town, where he met his surviving siblings, nieces, and nephews. He apparently does not wish to stay in Japan, viewing himself as a citizen of independent Ukraine; indeed, he has largely forgotten the Japanese language, which he hasn't spoken for 60 years.

The Times of London reminds us that "lost" Japanese World War Two soldiers have turned up in strange places before -- some, trapped at war's end on isolated Pacific islands or in the remoter parts of the Philippines, never learned that the war had ended and lived for years as hermits or guerillas. In some ways, however, the war disturbed Uwano's life far more than theirs. They never had to face the new realities of the postwar world: that Imperial Japan was dead, the hated Communists were triumphant throughout Eurasia, and no-one in the "Free World" cared what the Russians did to a few million German and Japanese prisoners. Ishinosuke Uwano was lucky: the great majority of the POWs conscripted by the Soviets in 1945 wound up in poorly-marked graves in Siberia. Uwano, at least, lived to see the fall of the Soviet Empire, the "Orange Revolution" in Ukraine, and his own homecoming.

Update, 10 June 2018: The Orwell story mentioned at the start of this post actually appeared in 1944, in the author's "As I Please" column. To the best of my knowledge, Ishinosuke Uwano remains alive.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Jefferson and the Beringian Migration