2006 concludes a four-year commemoration of the bicentennial of Lewis and Clark's overland journey to the Pacific Ocean. The two explorers have been back in the public eye for nearly a decade, owing to Stephen Ambrose's Undaunted Courage and Ken Burns' PBS series. The bicentennial commission has sponsored commemorative events along the Lewis andClark National Historic Trail, and the U.S. Mint has issued a series of commemorative nickels displaying a keelboat, a peace medal, a buffalo, and the Columbia Gorge. Naturally, our public remembrance of the explorers has been adulatory, emphasizing their courage, their scientific curiosity, and their sympathy for and good relations with the western Indians.

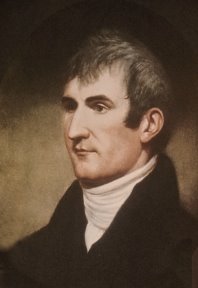

I think it useful to remember that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were only human, and that their personal shortcomings became particularly pronounced as they entered the last year of their journey. By 1806 Lewis and Clark were flea-bitten, footsore, exhausted, and homesick, and had lost all patience with the nominally-friendly Indians, even though their commission from President Jefferson had assigned them the dual role of explorers and diplomats. The highly strung Captain Lewis complained about acts of petty theft committed by members of the Wahclella and Eneeshur nations (in northern Oregon), whose beliefs about personal property -- i.e., that friendly people shared their goods with one another -- were very different from his own. In April Lewis beat up an Indian man who tried to steal "an iron socket of a canoe pole" and threatened his kinsmen with fire and sword if it happened again (John Bakeless, Journals of Lewis and Clark, 306-307).

A few weeks later, on May 5th, there was an even more noteworthy confrontation, stemming from Meriwether Lewis's acquired taste for dog meat. A young Nez Perce man "very impertinently threw a poor, half-starved puppy nearly into my plate by way of derision for our eating dogs, and laughed very heartily at his own impertinence." Rather than behaving diplomatically, Lewis responded violently: "I was so provoked at his insolence that I caught the puppy and threw it with great violence at him and struck him in the breast and face, seized my tomahawk, and showed him by signs if he repeated his insolence I would tomahawk him." (ibid, 313). The Nez Perces' replies to Lewis's action are not recorded. Neither is the puppy's.

Somehow, I doubt that Lewis's bloodthirsty threats, the fistfights, or the flung puppy will make it onto coins or into future television programs on the expedition. Americans need their myths, and the tale of the Corps of Discovery is the closest thing to the Odyssey that we have. On the other hand, a reader familiar with this story at least knows one fact that differentiates Meriwether Lewis from the more phlegmatic William Clark, whom most Americans otherwise tend to confuse with one another.

(There are some very good Websites on the Lewis & Clark expedition, including "Discovering Lewis and Clark.")

No comments:

Post a Comment