The fourth chapter of Niall Campbell Douglas Elizabeth Ferguson's (More) Civilization (Than You Deserve) is allegedly a discussion of the fourth "killer app" of Western civilization, medicine. An unwary reader might expect this to be an essay on medical science, focusing on breakthroughs like Jenner's smallpox vaccine. Those familiar with Professor Ferguson's style and beliefs will not be surprised to learn that it is instead a defense of European imperialism, with particular emphasis on its French variant, bookended by a gratuitous denunciation of the French Revolution* and an account of the First World War (about which Ferg says, with admirable originality, "War is Hell" [p. 187]). On the main subject of his chapter, Niall-o declares that French colonial public-health policy is a good answer to "those like Gandhi who maintained that the European empires had no redeeming features" (171). Through mandatory smallpox vaccination, the development of a yellow-fever vaccine, and the draining of malarial swamps, French officials significantly increased life expectancy in their African and Indochinese colonies, nearly doubling life-expectancy in the latter region between 1930 and 1960. There was certainly a downside to French health policy, Ferg admits, insofar as French officials used disease control as an excuse to segregate French colonists from the indigenes, thereby undermining the racial egalitarianism of their imperial vision. On the whole, however, the French imperium was the model of a good European empire, while the German empire in sub-Saharan Africa, with its draconian laws and exterminationist wars, was the model of a bad empire.

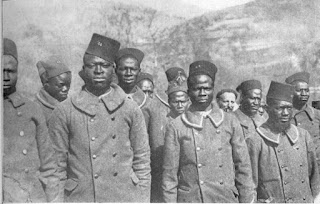

One must offer Ferguson some light praise for resisting the urge to write about one of his most favorite subjects, the British Empire, light of the world and land of the palm and the pine. One may then damn him for implying that there is such a thing as "good" imperialism. Every empire rests on the same original sin: the idea that there are certain races or ethnic groups or nations who are unfit to govern themselves, and who must therefore surrender their agency and destiny to another people. In theory, colonizers might be acting from benevolent intentions, such as the French "mission civilisatrice." In practice, imperial power attracts the cruel and the greedy, and empires therefore tend to become primarily instruments of exploitation. Ferguson acknowledges that European medical researchers weren't initially acting from benignly paternalistic motives: they were more interested in the survival of Europeans in tropical climates than in the well-being of colonial peoples. They focused their research on diseases that most affected Europeans, like malaria, rather than those that killed Africans, like "cholera and sleeping sickness" (174). Prof. Niall is less ready to acknowledge that colonial public health programs did not begin to affect colonized peoples' death rates until rather late in the colonial period - the 1930s and '40s - and that their primary goal, other than preventing the spread of disease to European settlers, was to ensure healthy workers for European mines and plantations and healthy soldiers for European armies.

Like other apologists for empire, Our Man Niall claims that policies intended to facilitate European exploitation were in fact enacted for the benefit of the "natives" - e.g. his observation that the French blessed Indochina with "20,000 miles of road and 2,000 miles of railways...coal, tin, and zinc mines, and...rubber plantations" (191), as if these were schools or cultural centers instead of money-making enterprises using cheap land and cheap labor. The positive effects of imperialism were fig leaves covering up the primary function of empire, which was to enrich a few Europeans, give the European lower and middle classes a false sense of racial superiority, and impoverish much of the world's population.**

Ferguson's imperialism is perhaps less obnoxious in this chapter than in his previous work about the British Empire (e.g. Empire, 2003) but it is still present, and one must wonder why. Partly, I think, Niall-o is still a British nationalist at heart, and longs for the days when Albion ruled 40 percent of the globe. There has also long been a strain of imperialism in Anglo-American conservatism that Ferg probably caught when he was a young Tory. This strain manifested itself in James Burnham's Suicide of the West (1964), which mourned the breakup of the European empires as a loss of territory by the Free World to the Communists; more recently, it appeared in Dinesh D'Souza's and Newt Gingrich's denunciation of Barack Obama's father for his "anti-colonial" views, which both men viewed as somehow anti-American. Ferguson's celebration of empire is a necessary compliment to this anti-decolonizationism. Finally, I suspect Professor Ferguson embraces pro-imperial views as something of a posture, an effort to appear contrarian, cheeky, and clever. What he forgets is Scalzi's Law: "The failure mode of clever is asshole."

* Our Man Niall does argue, in contrast to scholars like Simon Schama, that much of the violence of the French Revolution was a product of the French Revolutionary wars, not of the French Republicans' ideology.

** George Orwell observed that a penny was a common hourly wage in British India before the Second World War, and that an Indian laborer's leg was often thinner than a British person's arm.

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Thursday, May 17, 2012

The Country Where I Quite Want to Be

Your humble narrator has just returned from Finland, where he attended the biennial Maple Leaf and Eagle Conference in North American Studies at the University of Helsinki. As some of this weblog's readers may not have been to Finland, I will indulge in a few paragraphs' worth of travel writing, with the aim of wafting my readers off to that mysterious land of silks and spices (or at least of xylitol gum and reindeer).

There is much to like about Helsinki in early May. The city is clean and pleasant, its buildings painted in bright pastel colors. Helsinki's parks were green and free of snow, the trees just putting forth their first leaves. The weather for most of my stay was clear and sunny, with temperatures in the 50s. While chilly by Midwestern standards, this was warm enough that one could enjoy a beer or coffee out of doors at midday, and many of the locals did so.

As one might expect, Helsinki's people were ethnically homogenous: nearly all white and Northern European, except for a few Somali immigrants, East Asian tourists, and Romanian street musicians playing "When the Saints Go Marching In." Outside of the conference (where everyone was as casually friendly as conference-goers usually are), the Finns with whom I spoke were polite but reserved, and generally avoided making direct eye contact. Most spoke at least a little English, which is fortunate because the Finnish language was designed by aliens - it has 12 cases and virtually no cognates. (The Finnish word for "university," for instance, is "ylionpistu.") Apart from "kiitos" ("thank you"), I did not pick up ay Finnish words on the trip.

I am not qualified to say much about Finnish culture and society, except that they have the same fondness for ice hockey that Kentuckians do for basketball (i.e. it is the state religion), that their educational system is quite good but on the verge of budget cutbacks, and that a notable minority are partial to drinking heavily and howling in the streets at 3 AM. Just like college students, except they don't grow out of it.

Finland's national bird is, of course, an Angry one.

(The title of this post comes from this fine song by Monty Python.)

Thursday, May 03, 2012

The Rosy-Fingered Goddess Dawn

A Byzantine historian I know once told me he envied American historians their wealth of primary sources, even for under-documented periods like the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Classical historians, he noted, have at their disposal far fewer sources, many of them fragmentary, and can assume that no "new" documents on their subject will be discovered in their lifetime. Americanists, he concluded, can always write a book based on "new" documents, previously unseen by historians, whereas Classicists can only offer new interpretations. With respect to my friend, I must reply that interpretation lies at the heart of the historical profession, and that new interpretations of old stories are often much more interesting than new stories.

Take, for instance, the case of the Roman Emperor Caligula (12-43 CE), whom Anglo-Americans mainly know (thanks to Robert Graves and Bob Guccione) as an insane and sexually depraved tyrant who impregnated his own sister, then cut out and ate her fetus. In a new biography (U. of California Press, 2011) of the third Julio-Claudian emperor, Aloys Winterling argues that much of Caligula's apparently crazed behavior was actually a form of political satire, intended to keep a dissembling and sycophantic Senate in check. Caligula famously made his horse a senator, for example, not out of madness but as a critique of the Senate's self-aggrandizement. Similarly, when Caligula fell ill and a prominent senator offered his life to the gods in exchange for the emperor's, Caligula demanded his suicide to deter excessive flattery. Flattering the emperor, the author suggests, was the primary way individual senators jockeyed for power in the early imperial era, but as a result of competition for previous emperors' favor the political "coin" of flattery had become badly debased, to the point where ambitious senators were offering their lives on the emperor's behalf. In calling the senator's bluff Caligula was trying to "deflate" the currency of flattery and make the surviving senators more reserved in their praise. It is an intriguing argument, and one which makes sense of Caligula's abuse of the Senate. One might add, as reviewer Mary Beard has done (see the link above), that the early empire had no established rules of hereditary succession, and that Caligula had reason to assume that the more ambitious senators might aspire to the throne. In any event, Caligula died at the hands of several senators, and later imperial historians, such as Suetonius, treated him unkindly so as to flatter his successors by comparison.

What of Caligula's sexual deviancy? Mostly this was made up by Graves, Pulman, and Guccione, of course, though the famous story about his staffing a brothel with noble Roman women appears to have been true. Whether this makes him a tyrant or just a misogynistic asshole I leave to the reader's judgment. Myself, I would like to think he once dressed up as the Goddess Dawn and danced for his uncle Claudius, but regrettably historical reality is not always more interesting than fiction.

Take, for instance, the case of the Roman Emperor Caligula (12-43 CE), whom Anglo-Americans mainly know (thanks to Robert Graves and Bob Guccione) as an insane and sexually depraved tyrant who impregnated his own sister, then cut out and ate her fetus. In a new biography (U. of California Press, 2011) of the third Julio-Claudian emperor, Aloys Winterling argues that much of Caligula's apparently crazed behavior was actually a form of political satire, intended to keep a dissembling and sycophantic Senate in check. Caligula famously made his horse a senator, for example, not out of madness but as a critique of the Senate's self-aggrandizement. Similarly, when Caligula fell ill and a prominent senator offered his life to the gods in exchange for the emperor's, Caligula demanded his suicide to deter excessive flattery. Flattering the emperor, the author suggests, was the primary way individual senators jockeyed for power in the early imperial era, but as a result of competition for previous emperors' favor the political "coin" of flattery had become badly debased, to the point where ambitious senators were offering their lives on the emperor's behalf. In calling the senator's bluff Caligula was trying to "deflate" the currency of flattery and make the surviving senators more reserved in their praise. It is an intriguing argument, and one which makes sense of Caligula's abuse of the Senate. One might add, as reviewer Mary Beard has done (see the link above), that the early empire had no established rules of hereditary succession, and that Caligula had reason to assume that the more ambitious senators might aspire to the throne. In any event, Caligula died at the hands of several senators, and later imperial historians, such as Suetonius, treated him unkindly so as to flatter his successors by comparison.

What of Caligula's sexual deviancy? Mostly this was made up by Graves, Pulman, and Guccione, of course, though the famous story about his staffing a brothel with noble Roman women appears to have been true. Whether this makes him a tyrant or just a misogynistic asshole I leave to the reader's judgment. Myself, I would like to think he once dressed up as the Goddess Dawn and danced for his uncle Claudius, but regrettably historical reality is not always more interesting than fiction.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

The Virtual Chamber Pot War

To commemorate the forthcoming bicentennial of the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy is organizing a media and public-events campaign highlighting its role in the conflict. According to the Washington Post, these include a commemorative book and Twitter feed, a web video starring Richard Dreyfuss, several Tall Ships displays, and an interactive online game "allowing children to experience virtual life at sea by emptying chamber pots off the side of a ship." No, really.

The article notes that during the current era of defense cutbacks, the Navy is trying to use the 1812 bicentennial to revive public interest in its mission. This seems misguided to me on two counts:

First, Americans only care about two or three of their wars, and the War of 1812 isn't on the list. Americans remain fascinated by the Civil War, because many associate it with a chivalrous feudal civilization tragically crushed by a modern industrial society. (That this is a myth goes without saying, but most people prefer the legend.) We also like remembering World War Two because we got to fight Nazis, and because tanks and planes are fun. The Vietnam War is still remembered by Americans because it wrecked the lives of so many Baby Boomers, but few people in this country actually celebrate it. That's about all. No-one today much cares about the War for American Independence, as important as it was, because the causes for which the combatants were fighting seem arid and legalistic. The Mexican War and Spanish-American War remain largely forgotten, except that the latter evinces an image of Teddy Roosevelt in a cowboy hat. Modern Americans also care little about the First World War, the First Gulf War, and (pace M*A*S*H) the Korean War. The late unpleasantness in Iraq and Afghanistan will probably fade into obscurity in twenty years' time. And the War of 1812? Who cares, apart from me, Don Hickey, and the benighted Canadians? It was merely a three-year episode of incompetence and hooliganism, best forgotten by anyone who wants to retain any respect for the United States.

Secondly, the U.S. Navy actually performed rather badly in the War of 1812. Individual ships fared well in single-ship duels with British frigates, but the Navy as a whole could not prevent the Royal Navy from blockading the American coast and strangling the U.S. economy. The only strategic naval victory won by the U.S. during the war was the Battle of Lake Erie, which gave the U.S. control of that vital waterway during the 1813 campaign. Otherwise the Navy merely won a little glory while failing, as it was bound to fail (given Britain's overwhelming naval superiority), to defend the shores of the homeland. This is perhaps the wrong example to give to a Congress and a people who are growing tired of spending billions of dollars on nuclear-powered supercarriers, and who legitimately wonder what purpose such vessels serve in an era of drone warfare and terrorism. If the Navy wants to build support for its mission, perhaps it would be better off sticking to subliminal messages buried in boy-band music videos.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Niall Ferguson is Still Careless and Intellectually Lazy. Also, he's a Wanker

In the third chapter of Civilization for Me, But Not for Thee, Niall Campbell Douglas Elizabeth Ferguson addresses the relationship between property and liberty, with a sketchy comparison between (British) North America and Iberian South America. In North America, Ferg tells us, the "American dream" was, from an early date, "real estate plus [political] representation" (99), and for the most part migrants to the continent were able to achieve both. "Even the lowest of the low had the chance to get the first foot on the property ladder" (111), via land-grant clauses in indentured servants' contracts, local governments that secured property rights, and, after the American Revolution, through cheap land prices. (Secured through the subjugation or expulsion of the indigenous population, of course, but as we've noted before Niall doesn't particularly care about Indians.) Meanwhile, in Latin America, the "American dream" revolved around loot and martial glory, and the post-conquest elites were content to become the "idle rich" (113) while the Crown monopolized land ownership and the Indian, African, and mestizo populations stewed in poverty. Even after the nineteenth-century independence movement, economic inequality persisted, which destabilized the region's independent states: when populist insurgencies arose and demanded a more equitable distribution of property, landed elites backed dictators who would protect their wealth.

There is one hole which a reader could immediately poke in Our Man Niall's argument: among migrants to North America, "the lowest of the low" were black slaves, who had access neither to real estate nor political representation for 250 years. However, to his (limited) credit, Ferguson has anticipated this argument, insofar as he devotes the second half of the chapter to a comparative study of slavery and racial ideology on both continents. Whereas slaves in British North America were property for life, with very few opportunities to obtain their freedom, and whereas their post-Civil War successors were subject to a century of violent racism and marginalization, Latin American slaves sometimes had opportunities to earn their freedom, or to move their children up a more flexible racial hierarchy through interracial liaisons. (The latter were more violent and exploitative than I indicate here, but Ferguson doesn't mention that either.)

In thus shouldering the White Historian's Burden, Ferg provides himself with a convenient excuse for continued inequality in the United States - "social problems" engendered by slavery and Jim Crow continue to "bedevil...many Afro-American communities" today (138). That these problems may be due to persistent institutional and economic factors - white racism, eroding tax bases, and the monopolization of land and capital by a plutocratic white elite - are unpleasant facts that Niall generally prefers not to confront. His solution to the problem of inequality in the twenty-first century is a classic conservative one: at the microeconomic level, hard work and access to credit; at the macroeconomic level, privatization of state assets and export-led growth, to which he attributes Brazil's recent economic boom (139). Brazil actually doesn't prove Ferg's point, since it had higher rates of annual per capita income growth during the statist 1960s and '70s (4.5% per annum versus 1.3% in the '90s), and since its recent growth is largely due to public investments in education, transportation, and alternative energy. Meanwhile, the microeconomic proposal of More Banks for Everyone, which Ferguson made in a previous book, seems ill-advised given the similarities between modern Western bankers and "loan sharks." (Ha-Joon Chang, 23 Things They Don't Tell You about Capitalism [Bloomsbury, 2010], 55; Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money [Penguin, 2008], iv.)

Still, in this chapter Ferguson expresses views about inequality and racism that would prevent him, if he were a natural-born American citizen, from winning the Republican nomination for president. I cannot imagine giving him any stronger praise.

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Happy Leap Year

Given its rare appearance on the calendar, it is unsurprising that February 29th was seldom a day of great moment in American history. However, there are two significant events that occurred on Leap Year during the colonial era, both involving Puritans and Indians. The first (1692) was the formal filing of a legal complaint by Thomas Preston, Joseph Hutchinson, and Thomas and Edward Putnam of Salem Village against three women whom they accused of injuring their daughters and servants by witchcraft. The accused were Sarah Good, a woman "previously suspected of witchcraft by her neighbors," Sarah Osborne, a middle-aged woman involved in a land dispute with the Putnam family, and Tituba, a Native American slave. The three women set the pattern for what would become known as the Salem Witchcraft Trials or the Essex County Witchcraft Crisis, a crisis originating with legal disputes in Salem Village, actual belief in witchcraft, and fears of "devilry" left over from the Indian wars of the 1670s and early '90s. Before they was over, the trials would implicate 185 defendants (mostly women) from 22 towns and result in deaths of 20 people - all so that Salem could become a happening place on Halloween thenceforward. (Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil's Snare [Vintage, 2002], 8, 21-23, quote 23; see also Joseph Conforti, Saints and Strangers: New England in British North America [Johns Hopkins, 2006], 124-127.)

The other noteworthy event which took place on Leap Year in colonial New England was the Deerfield Raid of 1704, wherein a war party of Abenakis, Hurons, and Caughnawagas attacked the Massachusetts town of Deerfield, killing 50 people and taking another 100 captive. The raid led to one of the most famous captivity narratives of the colonial era, The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion (1707), written by the most prominent of the ransomed prisoners, Rev. John Williams. It also resulted in the decision by Williams' daughter Eunice to stay in Canada, convert to Catholicism, and marry a Mohawk man. Her grandson, Eleazar, led an equally famous life in the nineteenth century: educated by Congregationalists in New England, he went to Oneida country in 1816, successfully converted a number of Oneidas to Christianity, and became an advocate for voluntary removal of the Oneida nation to a new homeland in Wisconsin. Williams also asserted, later in his life, that he was the lost Dauphin of France, demonstrating that outrageous self-pronouncements were not merely the province of Anglo-Americans. (Conforti, 131-32; Karim Tiro, The People of the Standing Stone: The Oneida Nation from the Revolution through the Era of Removal [University of Massachusetts Press, 2011], 135-144.)

Labels:

Anniversaries,

Native New Englanders,

Puritans

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Aztecs and Samurai

In a post from my Voyagers to the East series, I noted that Hernan Cortes brought a dozen Aztec Indians to Spain in 1528 for presentation to Carlos I, and that several members of this cortege, whom Bernal Diaz described as jugglers and acrobats, wound up moving to Rome to adorn the court of Pope Clement VII. Courtesy of Charles Mann's fascinating book 1493, I have since learned that this was not the first party of Nahua to visit Spain: in 1526 Spanish priests had brought over another group of Mexican "jugglers," who turned out to be skilled players of the game of ullamaliztli. The Venetian ambassador to Spain reported on the ball players' padded garments and on the immense speed and dexterity with which they propelled the ball to the goal. The purpose of the game puzzled the ambassador, but more puzzling still was the ball itself, made of some sort of "pith" that caused it to jump about. The pith was actually rubber, which Europeans had never seen before, and the ball's behavior was such that the ambassador couldn't describe it because there was no precise word in contemporary Italian for "bounce."* (Charles Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created [Knopf, 2011], 240-42.)

* The English word "bounce," per the Oxford English Dictionary, existed but was not used to describe the bouncing of a ball until the seventeenth century.

Jarring juxtapositions like this one are among the more compelling features of Mann's narrative. Another, more jarring (and fascinating) example of this trope occurs in Mann's discussion of Asian migration to colonial Mexico, which apparently was quite substantial in the seventeenth century. Spanish treasure ships had begun regular voyages across the Pacific in 1565, stopping in Manila to exchange Mexican and Bolivian

silver for Chinese silk and porcelain. Apparently, many of these vessels brought Asian immigrants back with them to Latin America. The 100,000 or so trans-Pacific travelers included Japanese emigrants who had been stranded in China or the Philippines when the Tokugawa regime sealed the home islands' borders. A few of these were samurai whom the viceroy allowed to retain their katanas and employed in Mexico's colonial militia. I am fairly certain I made the previous sentence up. (Hastily checks book.) Nope, there it is on page 324. Mann cites a recent article by Edward Slack, who identifies the countries of origin of colonial Mexico's chino population (China, the Philippines, Japan, India), describes their professions, and observes that Asians were the only non-whites in Mexico licensed to carry weapons and serve in the colony's militia. (See Edward R. Slack, Jr., "The Chinos in New Spain: A Corrective Lens for a Distorted Image," Journal of World History 20 [Winter 2009], 35-67.) Professor Slack does not offer suggestions for how one might turn this fascinating story into a film plot, but such a movie script (perhaps a mashup of Yojimbo and Treasure of the Sierra Madre) almost writes itself.

* The English word "bounce," per the Oxford English Dictionary, existed but was not used to describe the bouncing of a ball until the seventeenth century.

Labels:

Aztecs,

East Asia,

Games,

Indians in Europe,

Pacific History

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Niall Ferguson is Still a Rotter

In the second chapter of Civilization According to Niall Campbell Douglas Elizabeth Ferguson, the author discusses the "killer app" of Science, and how it explains the expansion of Western civilization relative to the Rest of the World - to the Islamic World, in particular. The most powerful Islamic empire of the early modern period, Ferguson observes, was the Ottoman, which dominated the Middle East, North Africa, and southeastern Europe, and whose armies twice laid siege to Christendom's eastern bastion, Vienna. The second of these sieges, however, ended in what turned out to be a "long Ottoman retreat," as the empire was undermined, apparently, by its inability to replicate European science and technology. In the Muslim world, Professor Niall tells us, there was no separation of church and state, and the former had paramount power in matters of the mind; if religious leaders denounced European innovations as blasphemous, the state had no choice but to suppress them. In Western Europe, meanwhile, Europeans benefited from a lack of Church restraint on science, from state support for science in the form of royal scientific societies (an important point, actually), and from the printing press, which allowed scientists widely to disseminate their findings. (Also helpful, though Ferguson doesn't mention it, was a common learned language, namely Latin, which allowed researchers from different nations to communicate.) The result was a "scientific revolution" that made Europe more powerful, in the long run, than the Ottomans and other Islamic states, even though the Ottoman Empire routinely tried to copy Western technology and military science in the 1700s and 1800s.

The biggest problem with this chapter is Ferguson's failure to establish a convincing connection between science and state power, apart from a two-page digression on the scientist Benjamin Robins and his invention of the science of ballistics. Artillery is important, but inferior artillery and underdeveloped technology were not the most important causes of the Ottoman Empire's decline. Our Man Niall actually identifies one of these later in the chapter: inefficient taxation and the consequent inability of the Ottoman regime to pay for a modern army without heavy borrowing, at usurious rates, in Europe (p. 89). Another cause of Ottoman distress was the empire's loss of the northern shore of the Black Sea to Russia (ca. 1768-91), which opened the possibility of a Russian seaborne assault on Constantinople and diverted precious Ottoman resources to home defense. In sum, it was those old culprits, imperial overstretch and financial difficulties, that sickened the Sick Man of Europe.

Along the same lines, the Sexiest Scotsman fails to demonstrate persuasively the relationship between European science and European power. He discusses ballistics and rifled artillery, of course, but neither had much of an impact on European war-making until the mid-nineteenth century. May I suggest that a more important European scientific discovery than ballistics was the discovery of atmospheric pressure and the energy that one could generate by creating a vacuum? (I believe I may.) In the seventeenth century Otto von Guericke discovered that an evacuated sphere could not be pulled apart by two teams of horses, and in 1680 Christian Huygens proposed generating a vacuum in a piston to perform work. Guericke and Huygens' experiments helped lead to the first functional steam engines, which used a partial vacuum, generated by condensing steam, to produce a 5-horsepower "power stroke." Thomas Newcomen, who designed said engine, doesn't seem to have read about Guericke and Huygens' work, but his predecessors, Denis Papin and Thomas Savery, had certainly done so. Some decades later the inventor Nicholas Appert made another important discovery about vacuums, which is that a vacuum combined with high levels of heat helped inhibit organic decay. Appert applied this insight to the invention of canned food. The steam engine made steam-powered transport possible, and facilitated the mass-production of consumer goods like clothing. Canning made it possible adequately and reliably to feed very large non-rural populations, like city-dwellers and soldiers. Both technologies helped turn Europe into the most urbanized and industrialized part of the world by 1900. This, I would argue, was a more vital component of European power than big guns.

Why doesn't N.D.C.E. Ferguson spend more time discussing the relationship between scientific research and economic (and military) power? I suspect this is because he doesn't actually know that much about science, a pity given the premise of this chapter. Rather than describe the accomplishments of the European Scientific Revolution, Ferguson contents himself with summarizing the 29 "most important scientific breakthroughs" of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries (65-66), discoveries which are apparently important because the author tells us so, not because he explains their impact on Europeans' worldview and approach to the physical world. Much of the rest of the chapter is devoted to Ferguson's summary of Bernard Lewis's book on Islamic scientific backwardness, along with a paean to Ferg's Secret Boyfriend, Frederick II of Prussia, and a somewhat overwrought linkage of modern Israel with seventeenth-century Vienna - Jerusalem, he writes, is "the modern equivalent of Vienna in 1683" - accompanied by dark mutterings about the threat posed to Israel by the sinister lights of Perverted Muslim (Nuclear) Science. It’s worth noting that Ferguson’s curious reference to the 1683 Siege of Vienna is a “dog-whistle” to some conservative European nationalists, who believe that Christendom is once again under siege by the Turks – this time, by Turkish guest workers and by Turkey’s drive to win admission to the EU. Professor Niall, to his credit, tells these European nativists that they have nothing to fear from the Turks, who began "downloading" European secularism in the 1920s. Instead, they need to worry about defending Israel, the Besieged Vienna of the twenty-first century, from the nuclear forces of the devilish Iranians. This effort to create an alliance between old European nationalist conservatives and American neo-conservatives appears to be Ferguson's chief intellectual goal in this chapter. That's the Scientific Method, you see.

Sources: Bernard Lewis, What Went Wrong? The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East (Harper Perennial, 2003); John Darwin, After Tamerlane, 174-75; Alfred Crosby, Children of the Sun, 71-76; Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World, 1776-1914 (Grove Press, 2007), 50-52; Andrew Wheatcroft, The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Struggle for Europe (Basic Books, 2008), 266-267; Tom Standage, An Edible History of Humanity (Walker and Company, 2009),159-163; Niall Ferguson, Civilization, 50-95.

Tuesday, February 07, 2012

Napoleonland

The Telegraph and the Times of London report that former French Cabinet minister Yves Jego is planning an amusement park commemorating the life and times of Napoleon Bonaparte. The proposed park will include a daily re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo, a Trafalgar water show, a ski run commemorating the retreat from Moscow (complete with fake bodies in the snow), and a re-creation of the guillotining of Louis XVI. Other attractions* may include an ice-skating rink where park visitors can shatter the ice and drown other tourists with cannon, an Egyptian pavilion where customers may buy pastries shaped like the Sphinx (provided they agree to bite off the noses) , a tunnel-of-love ride where an animatronic Napoleon shares his most romantic sentiments (e.g. "Don't wash; I'm coming home" or "I wish to marry a womb"), a coffee bar named "Damn Coffee, Damn Sugar, Damn Colonies," a regular bar where one may buy Whiff of Grape (TM) alcopop by the shot, and a Saint-Helena-themed hotel where guests are obliged to listen to has-been French politicians boast about their former accomplishments, or (if they visit the adjoining Elba lounge) lament their current isolation, preferably in the form of a palindrome.

Napoleonland is supposed to open in 2017, provided Jego and his associates can raise the 200 million Euros it will ostensibly cost - and provided no-one in Las Vegas beats them to the draw.

* Which I believe I made up.

Napoleonland is supposed to open in 2017, provided Jego and his associates can raise the 200 million Euros it will ostensibly cost - and provided no-one in Las Vegas beats them to the draw.

* Which I believe I made up.

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

Niall Ferguson is Still a Colossal Muttonhead

The first chapter of Niall Campbell Douglas Elizabeth Ferguson's Civilization discusses the first "killer app" of Western civilization, competition, and introduces the device he uses throughout the book to make his arguments, the poorly-crafted comparison. One can clearly see the benefits of interstate competition, Our Man Niall asserts in this chapter, by comparing the navigational and military achievements of Western Europe with those of Imperial China. In the fifteenth century Ming China was a rich, urbanized and technically sophisticated country, capable of sending huge "treasure fleets" across the Indian Ocean. By the middle of that century, however, the Ming emperor decided to turn his back on oceanic exploration, and because there were no rival powers to gainsay him the entire Chinese population had to follow suit. China as a result slipped into isolationism, economic stagnation, and disorder, which apparently lasted until the twentieth century.

Meanwhile, the states of Western Europe, divided by geography into a multiplicity of competing states, were driven by their own rivalries to develop new navigational techniques and ships capable of reaching the Americas or East Asia (pp. 33-34). These competitors also developed improved cannons, one of the keys to their penetration of Asian markets, and - here one must give Ferg credit for a useful insight - devised systems of public finance capable of paying for hundreds of ships and cannon. The same interstate rivalries and navigational techniques also impelled and allowed Europeans to colonize the Americas, which, Ferguson notes - forgetting how dismissive he was of this point in his Introduction - provided Europe with an outlet for unwanted people and with "new nutrients like potatoes and sugar" (45), assets that China did not enjoy. Navigation and the interstate competition that fostered it were not the sole sources of early modern European power, but they certainly gave Europeans an advantage over a torpid and declining China.

Well, perhaps. It all depends on which China you're talking about. Our Bearer of the White Man's Burden reports that the Ming Dynasty collapsed in civil war and famine in the mid-seventeenth century, and that thereafter China remained "stationary" (46) until the twentieth century. This is bilge. The Manchu invaders who occupied Beijing in 1644 went on to create a dynamic polity and society in China in the eighteenth century. The imperial army conquered Formosa, Tibet, and eastern Turkestan, expanding China to its modern borders; the amount of arable land under cultivation doubled between 1720 and 1780, as Han Chinese colonized lightly-settled regions within the empire's borders; and the empire's population also doubled during the same period, to more than 300 million. Meanwhile, the Qing government repaired and expanded China's system of canals, lowered taxes, abolished serfdom, and lifted restrictions on land sales. By eighteenth-century European standards it was a model of "enlightened despotism.”

Nor was China an isolationist state during the 1600s and 1700s. No-one tried to build a fleet comparable to Zheng He's again - in part because China didn't have enough exploitable timber to keep building enormous oceanic ships - but Chinese traders used smaller vessels to join the Indian Ocean trading network at Melaka, and the Qing government allowed Europeans to establish trading posts at Canton and Macao. Qing China used these connections indirectly to exploit the riches of the New World: at least 30 percent of the silver and gold from Spanish America was shipped to China, to pay for silks, sugar, tea, and other goods that the Chinese produced for export. At the same time, Chinese peasants acquired American crops like sweet potatoes and maize and used them to cultivate the empire's central and western uplands. Certainly, China stagnated around the end of the 1700s, as it reached the limits to growth set by elite conservatism, soil erosion, and a lack of energy resources, but this occurred at the end of 150 years of growth, not as a continuation of a 200-year-old trend.

Ferguson organizes his book both chronologically and thematically, which means that he intends in each chapter to cover a distinct and sequential epoch in world history - in Chapter One, the period from 1400 to 1650. However, he goes out of his way to indicate, through scattered references to Chinese stagnation and complacency in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that Chinese history essentially stopped in 1650, and didn't restart (in an economic sense) until the Maoist revolution. A nation's history, however, doesn't just stop because you've ordered it to do so for the sake of narrative convenience. Maybe Ferguson should sue the Qing Dynasty for complicating his story.

[Sources: Gale Stokes, "The Fates of Human Societies," American Historical Review (April 2001): 508-525, esp. 514, 516-18; Jeremy Black, Warfare in the 18th Century (Smithsonian, 2005), 31-39; John Darwin, After Tamerlane: The Rise and Fall of Global Empires, 1400-2000 (Bloomsbury, 2008), 129-131; Kenneth Pomeranz, "Their Own Path to Crisis? Social Change, State-Building, and the Limits of Qing Expansion, c. 1770-1840," in The Age of Revolutions in Global Context, c. 1760-1840, ed. David Armitage and Sanjay Subrahmanyam (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), 189-208, esp. 192-194; Niall Ferguson, Civilization (Penguin, 2011), 19-49; Charles Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (Knopf, 2011), 162-192. Thanks to commenter John for recommending the last title.]

Thursday, January 26, 2012

New Rules

Periodically, when the American federal government undergoes an especially grievous episode of gridlock, incivility, or general craziness, I am prone to wishing we could simply scrap our ancient and seizure-prone federal Constitution and turn Washington, D.C. into a theme park. Reason, however, tells us that just as Nature abhors a vacuum, so would human beings find it difficult simply to raze the American national government without building a replacement – and that nowadays a new federal constitution would be likelier to draw its inspiration from Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins than from James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. In the interest of providing an alternative to a Christian Dominionist government, I herewith offer, with tongue somewhat in cheek, my own outline of a replacement constitution. Comments are welcome so long as they amuse me.

Dave’s Constitution:

1. All persons residing in the territory or jurisdiction of the United States are entitled to the equal protection of its laws.

2. All persons born or naturalized in the U.S. are U.S. citizens and entitled to the privileges and immunities thereof.

3. Neither the U.S., the states, nor any subordinate jurisdiction may abridge freedom of speech, the press, the rights of peaceable expression and assembly, and the right to petition officials for redress of grievances.

4. Neither the U.S., the states, nor any subordinate jurisdiction may abridge religious freedom or provide any legal or financial support to any religious entity.

5. No American citizen over the age of 18 may be deprived of the right to vote for any reason.

6. Neither the U.S., the states, nor any subordinate jurisdiction may infringe the right of persons to secure enjoyment of their homes, businesses, persons, and possessions.

7. The U.S. government, the states, and all subordinate jurisdictions guarantee the rights of habeas corpus, due process of law for those accused of a crime (including the right to an attorney and compulsory appearances of witnesses), and immunity from cruel and unusual punishment, including the death penalty, "stress positions," and waterboarding. Up yours, Dick Cheney.

8. The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall extend to all weapons invented prior to 1791, including smooth-bore, black-powder cannon. Private citizens owning wooden, sail-driven ships of war may not engage in privateering without a Congressional letter of marque and reprisal.

9. The old Ninth Amendment is pretty awesome, so let's keep that.

10. The executive of the United States shall consist of a president, elected by majority vote of the citizens of the United States every four years; a vice-president (ditto), who shall succeed the president in the event of his or her death or resignation; and such subordinate officers as Congress may authorize by law. All will be bound by oath to support this Constitution and faithfully execute the laws of the United States.

11. The vice president, just to clarify, is part of the executive branch. Up yours, Dick Cheney.

12. Any U.S. citizen (born or naturalized) may run for president or vice-president, provided they are at least 35 and have been a resident of the United States for at least 20 years.

13. The president shall have the power to veto federal legislation, but not to alter or amend such legislation.

14. The legislative branch of the U.S. shall consist of a single legislative house, the Congress of People's Deputies. The voters of each electoral district will elect one Deputy every two years, for a two-year term, with vacancies to be supplied by special election. Each Deputy must be a U.S. citizen and at least 30 years of age.

15. The legislature shall have the exclusive right to levy federal taxes, print or coin money, borrow money on the credit of the United States, and declare war. It may approve treaties, Constitutional amendments, or impeach and remove the president by 3/5 vote. It shall have plenary authority to regulate foreign and interstate commerce, up to and including the nationalization of American businesses.

16. It should go without saying, but corporations are not people.

17. The U.S. and state governments will provide free public education and health care to all U.S. citizens and permanent residents. The standard of health care service provided will be no lower than that afforded participants in the Medicare program before it was terminated by President Rand Paul.

18. All federal and state elections shall be publicly financed. No private money may be spent therein, except by George Will, who may spent $5.00. No, not five dollars a year. Five dollars period.

19. The judicial branch of the United States shall consist of a Supreme Court and such inferior courts as Congress may establish. All federal judges will be elected by the voters of their jurisdiction for a 7-year term, renewable.

20. This Constitution may be amended by a 3/5 vote of the Congress of People's Deputies, with the concurrence of a 3/5 plebiscitary vote of American voters, to be conducted by the states under federal guidelines.

21. The official anthem of the United States will be a mashup of Miley Cyrus’s “Party in the U.S.A.” with Notorious B.I.G.’s “Bullshit and Party.” This clause is not subject to the amendatory authority in 20, above.

22. The capital of the United States will be moved to Omaha, Nebraska. The capitol itself, along with the president's mansion and principal executive office buildings, will be located in Carter Lake, Iowa, which, being located wholly within Omaha's boundaries, accurately represents the duality of Man.

23. The official flag of the United States shall be a red banner bearing a portrait of Eugene V. Debs.

24. The official motto of the U.S. will be “Up Yours, Dick Cheney."

Friday, January 20, 2012

Dress to Kill

Our quote of the week comes from R.R. Palmer's classic study of the Reign of Terror, Twelve Who Ruled, and concerns the twenty special commissioners whom members of the Committee of Public Safety appointed to oversee the political reconstruction (and destruction) of Lyons, after that city rebelled against the Republic:

"The commissioners were apparently in need of clothing, and their wants were not modest. For each one, out of the public funds, were ordered, to be exact: a blue coat with red collar, blue trousers with leather between the legs, breeches of deerskin, an overcoat and leather suitcase, a cocked hat with tricolor plume, a black shoulder-belt, various medals, six shirts, twelve pocket handkerchiefs, muslin for six ordinary cravats, black taffeta for two dress cravats, a tricolored belt, six cotton nightcaps, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of shoes, kid gloves a l'espagnole, boots a l'americaine, bronzed spurs, saddle pistols and a hussar's saber." (Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution (Princeton UP, 1941/2005), 167.)

Palmer includes these details to make a more entertaining narrative. Modern historians, following the lead of Linda Colley, might pause to consider the social significance of the commissioners' wardrobes. The colored coat and trousers, cocked hat, and handkerchiefs were marks of a gentleman (or at least of someone rich enough to afford clothing of high-quality fabric); the spurs, boots, pistols and saber denoted a member of the nobility, or at least one qualified to ride and bear arms; the tricolored belts and plumes symbolized the republic; and the deerskin breeches were fashionable at the time and probably came from North America. The Committee on Public Safety may have wanted the special commissioners to appear as modest sans-culottes adorned in virtuous homespun, but the officials themselves had other ideas: they came to Lyons as armed noblemen, ready to ride down their government's enemies. Which indeed they did: the commissioners went on to execute over 2,000 people in France's second city. Maybe the "blue trousers with leather between the legs" were chafing them a bit too much.

(The awesome anime painting of Louis Antoine Saint-Just is courtesy of Ysa, from Deviant Art, and is used with permission of the artist. Copyright (c) 2008-12 by Ysa.)

Friday, January 13, 2012

Niall Ferguson is Still a Tosser

After flogging Niall Campbell Douglas Elizabeth Ferguson a couple of times last year for various kinds of bad behavior, I made a brief mention of plans to read Prof. Ferguson's macrohistory of Western Europe and how it got to be So Damn Fine, published last year under the modest title Civilization. My loyal readers will either be mildly pleased or politely indifferent to learn that I have now managed to plow through most of the Sexiest Scotsman's opus, and will shortly begin a multipart review in which I explore the strengths (there may be one or two), flaws (and there are at least a few), and amusing factual errors thereof and therein. To start, I have a couple of observations to make about Ferguson's preface and introduction.

First, allow me to draw attention to Our Man Niall's brief summary of other scholarship on the rise of the West. On page 10 he asserts that historians like Jared Diamond and Kenneth Pomeranz have attributed the growth of Western power to simple "good luck," rather than to Western Europeans' superior institutions - in Ferguson's phrase, their "killer apps." The examples he gives of this unlikely "good luck," however, seem like pretty important determinants of European power to your humble narrator, and as Ferguson later reveals some of them seem pretty important to him as well. Surely, Ferguson writes, it was not the "geography or the climate" of Europe that accounted for its rise - except that he later ascribes interstate competition in the West, a key component of Killer App Number One, to Europe's convoluted and knobbly geography. "Did the New World provide Europe with 'ghost acres' that China lacked?" Professor F. then asks, dismissively. Actually, it did; the resources and produce of the Americas - arable land, timber, fish, grains, sugar - were a tremendous boon to Europeans in the early modern period, rescuing them from the Malthusian trap into which they had fallen. Meanwhile, New World gold and silver helped Europe buy its way into the Indian and East Asian trading system. "Was it just sod's law that made China's coal deposits harder to mine and transport than Europeans'?" Dr. Ferguson inquires. Kind of sounds like it to me, actually, and it was Europe's use of cheap coal that touched off its transport and metallurgical revolutions and allowed it finally to pull ahead of China. Qing China certainly had the means to industrialize if it had enjoyed access to so much concentrated energy: the Chinese had had a wood-driven "industrial revolution" in the eleventh century, until their foundries ran out of charcoal, and they had invented powered spinning machines and looms as early as the fourteenth century. In history, stupid contingencies sometimes matter, as Ferguson, a routine practitioner of counterfactual history, should bloody well acknowledge.

My other observation is short and sweet. It is that Ferguson isn't always careful to check his historical facts. Exempli gratia, taken from his preface: "The greatest political artist in American history, Abraham Lincoln, served only one full term in the White House, falling victim to an assassin with a petty grudge just six weeks after his second inaugural" (xxiv). The assassin was John Wilkes Booth, and the "petty grudge" was the "Civil War" - Booth was a Confederate spy and staged his attack on Lincoln as part of a multi-person attack on Union leaders. Perhaps Ferguson was confusing Booth with Charles Guiteau, Garfield's assassin? I guess all these nineteenth -century presidents look alike after a while.

(Sources: Gale Stokes: "The Fates of Human Societies: A Review of Recent Macrohistories," American Historical Review [April 2001]: 508-525; Alfred Crosby, Children of the Sun: A History of Humanity's Unappeasable Appetite for Energy [Norton, 2006], 68; Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest [Penguin, 2011], pp. xxiv, 10.)

First, allow me to draw attention to Our Man Niall's brief summary of other scholarship on the rise of the West. On page 10 he asserts that historians like Jared Diamond and Kenneth Pomeranz have attributed the growth of Western power to simple "good luck," rather than to Western Europeans' superior institutions - in Ferguson's phrase, their "killer apps." The examples he gives of this unlikely "good luck," however, seem like pretty important determinants of European power to your humble narrator, and as Ferguson later reveals some of them seem pretty important to him as well. Surely, Ferguson writes, it was not the "geography or the climate" of Europe that accounted for its rise - except that he later ascribes interstate competition in the West, a key component of Killer App Number One, to Europe's convoluted and knobbly geography. "Did the New World provide Europe with 'ghost acres' that China lacked?" Professor F. then asks, dismissively. Actually, it did; the resources and produce of the Americas - arable land, timber, fish, grains, sugar - were a tremendous boon to Europeans in the early modern period, rescuing them from the Malthusian trap into which they had fallen. Meanwhile, New World gold and silver helped Europe buy its way into the Indian and East Asian trading system. "Was it just sod's law that made China's coal deposits harder to mine and transport than Europeans'?" Dr. Ferguson inquires. Kind of sounds like it to me, actually, and it was Europe's use of cheap coal that touched off its transport and metallurgical revolutions and allowed it finally to pull ahead of China. Qing China certainly had the means to industrialize if it had enjoyed access to so much concentrated energy: the Chinese had had a wood-driven "industrial revolution" in the eleventh century, until their foundries ran out of charcoal, and they had invented powered spinning machines and looms as early as the fourteenth century. In history, stupid contingencies sometimes matter, as Ferguson, a routine practitioner of counterfactual history, should bloody well acknowledge.

My other observation is short and sweet. It is that Ferguson isn't always careful to check his historical facts. Exempli gratia, taken from his preface: "The greatest political artist in American history, Abraham Lincoln, served only one full term in the White House, falling victim to an assassin with a petty grudge just six weeks after his second inaugural" (xxiv). The assassin was John Wilkes Booth, and the "petty grudge" was the "Civil War" - Booth was a Confederate spy and staged his attack on Lincoln as part of a multi-person attack on Union leaders. Perhaps Ferguson was confusing Booth with Charles Guiteau, Garfield's assassin? I guess all these nineteenth -century presidents look alike after a while.

(Sources: Gale Stokes: "The Fates of Human Societies: A Review of Recent Macrohistories," American Historical Review [April 2001]: 508-525; Alfred Crosby, Children of the Sun: A History of Humanity's Unappeasable Appetite for Energy [Norton, 2006], 68; Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest [Penguin, 2011], pp. xxiv, 10.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)